Notes

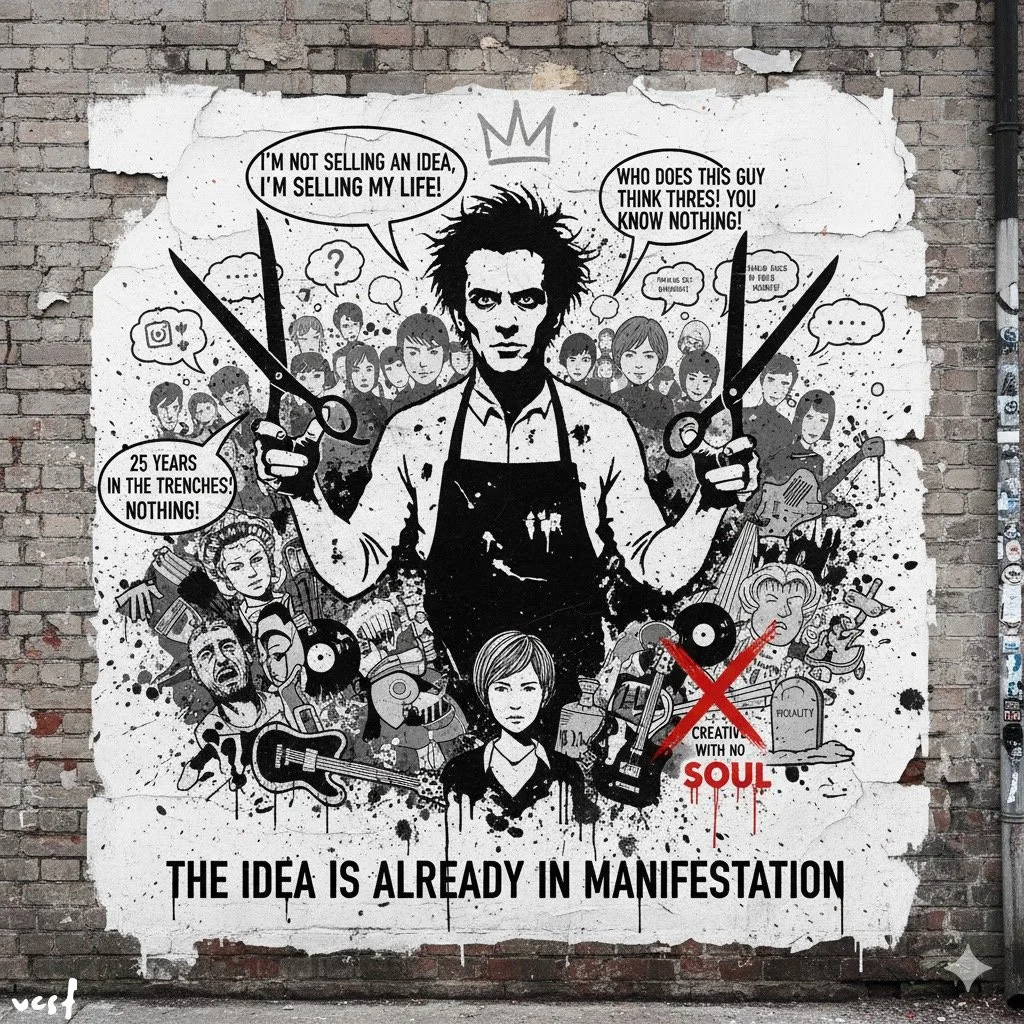

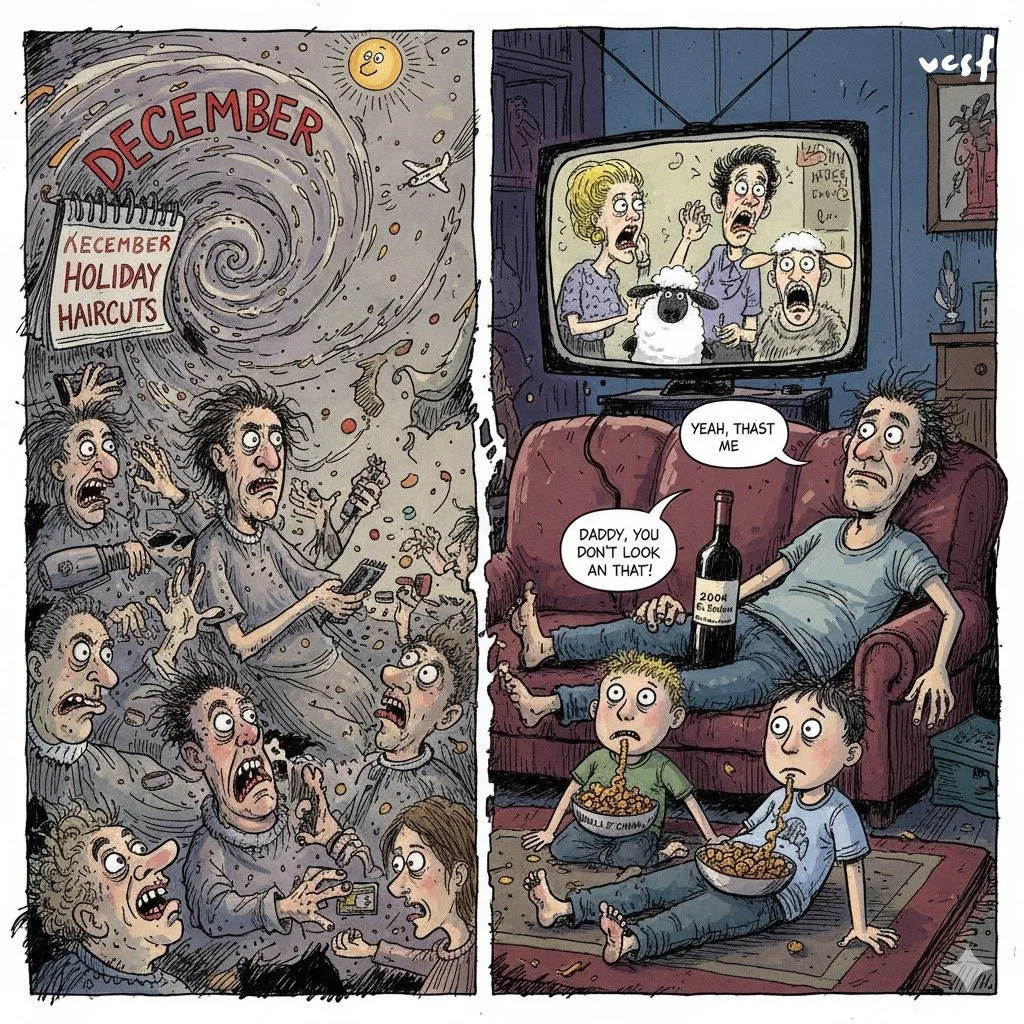

The Anthony Bourdain of Hairdressing

Five years ago, I found a copy of Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential in a local charity shop. I had no idea who he was, but the back cover hooked me instantly. I devoured the book, taken in by his honesty, his humour, and his unapologetic opinions. But what truly resonated with me was his story. In many ways, it was just like mine. The Bourdainian chef, sweating under the fluorescent-hot lights of the line, grease coating the worn tiles, is a creature of raw adrenaline and cynicism. His world, as immortalised in Kitchen Confidential, is a rock ‘n’ roll ballet of debauchery, high-wire acts, and the brutal, silent language of knives and heat. But step away from the inferno of the deep fryer and into the climate-controlled cacophony of the hair salon—the kingdom of the stylist, the domain of the hairdresser—and you find the identical soul, merely wearing a different uniform.

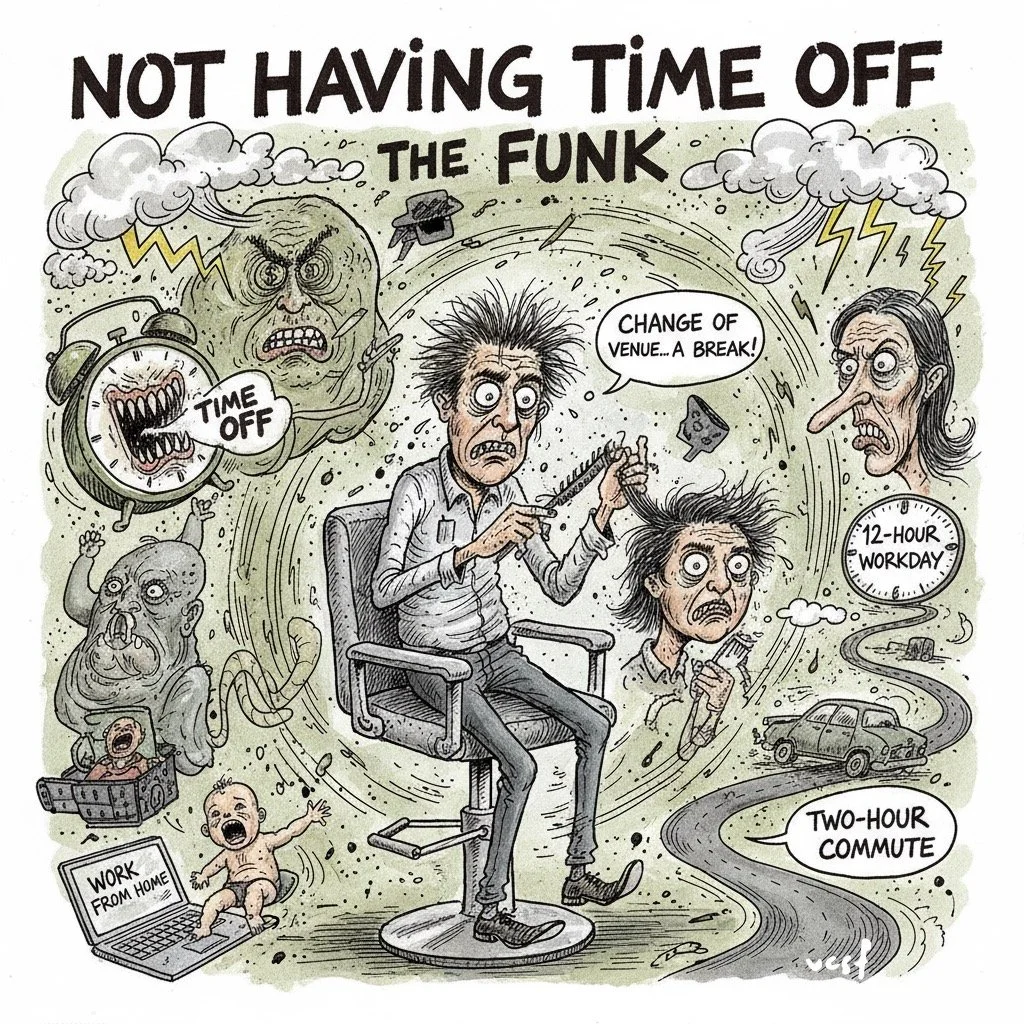

The adrenaline rush and the necessary escape watches the kitchen runs on tickets, slams, and the ticking clock of service. Every minute is a crisis, every plate a potentially career-ending failure. This manic energy demands an equal and opposite release. For Bourdain and his ilk, the post-shift ritual was often salacious and swift: the late-night drinking, the dive bars, the stories traded—a temporary suspension of consequences born from knowing you cheated death for one more shift.

In the salon, The stylist, perpetually on their feet, smiling through client trauma, executing precision cuts while selling product, lives the same adrenaline curve. It is the silent, shared understanding with colleagues that breeds the same high-tempo, rock ‘n’ roll need for relief. The back alley smoke break the same debauchery, fueled by the same exhaustion, The Underbelly and The Confessional. Bourdain pulled back the kitchen’s curtain to reveal its honest, vulgar underbelly: the shortcuts, the drug use, the strict, unforgiving hierarchy. He found truth in the dirt.

The salon has its own, visible only to those who work there. The salacious stories here are whispered into mirrors. The hairdresser is the ultimate confessional, absorbing every marital crisis, every career failure, every self-loathing pronouncement. They hold secrets like a vault, often more intimately connected to their client’s vulnerability than a spouse or therapist. We are both, the chef and the stylist, tradesmen who deal in human desire: the desire for sustenance, and the desire for self-reinvention. Both are transactional, and both are brutally honest. The highest highs and the lowest lows are identical. The chef’s ultimate high is the perfect plating—that brief, transient moment of edible perfection before the food is consumed and forgotten. The stylist’s high is the total transformation. the client sees a better version of themselves in the glass. It is a moment of pure, fleeting creation.

The failure is also shared. The burnt sauce, the under-cooked protein, the plate sent back—it’s the chemical burn, the haircut gone rogue, the colour that went too dark. These failures are public, immediate, and must be absorbed. The failing ideology is the same: the job demands perfection, the human provides only excellence, and the constant striving leaves its mark—on the chef’s scorched arms and the hairdresser’s aching feet and carpal tunnel.

Bourdain’s legacy is a testament to the honesty of the working class artisan, the one who finds grit, truth, and beauty in the least-expected places. Whether you are navigating the scorching "hot zone" of the line cook or performing therapy and physics in the "high chair" of the salon, the core ideology remains: you are a maker, a fixer, a cynical optimist who believes in the redemptive power of the next creation. You are a professional observer of humanity, and you know, better than anyone, that the real stories are found far below the surface, in the chaos of creation. AB once said '‘Meals make the society, hold the fabric together in lots of ways that were charming and interesting and intoxicating to me. The perfect meal, or the best meals, occur in a context that frequently has very little to do with the food itself.” In the same way o feel the same way about the exchange between hairdresser and client.

As I absorbed his commentary on the restaurant world, a thought kept nagging at me: why had no one written a book like this about hairdressing? We all use this industry, yet we have no real understanding of what it entails. There are no books that get to the heart of what it's like to be a salon hairdresser. Who are the people cutting our hair? What is this job really about? No one has ever accurately described the dexterity, the creativity, and the sheer physicality involved, let alone the ins and outs of the industry itself.

Bourdain lifted the lid on the opaque world of kitchens two decades ago, and now everyone is obsessed with chefs and restaurants. Yet hairdressing remains surprisingly obscured from view. Hairdressers, however, have stories to tell. Their world is populated by them. They have access to every industry imaginable, with the experiences of thousands walking through their doors. They engage in conversations on subjects they'd never considered, all while working with the focus and precision of a maestro. Imagine the stories a hairdresser could tell you.

Marcus’s paradox. Everyone is welcome, but I don’t want everyone.

For twenty years, I’ve been a hairdresser. I’ve worked in luxury five-star salons and small, back-street independents. I’ve trained at the highest level and worked with global icons. I’ve been an assistant, a boss, and now I run my own salon. My writing comes from this experience and from the heart. My pieces are about the job—the good, the bad, and the downright shameful. They are also, of course, about my clients. Not their private lives—I would never betray that sacred trust—but about managing those complex relationships. My word is my bond, and the confidentiality I have with them is paramount, but there is enormous fodder for scrutiny, insight, and humour.

I use my experiences with some of my more challenging clients to explore how people view themselves and the world. It’s always a humbling experience. I try to voice my opinion without pushing my views on my clients, which is a fine balance. If I were to assess my clients based on their politics and beliefs, I’d probably be left with a skeletal client base. It takes an enormous amount of patience and skill to manage your own political boundaries alongside those of your clients.

But for every challenging client, there is an equal number that I adore—the ones who make it all worthwhile. They have made my job an essential part of who I am. Many have been with me for my entire career, loyally following me from salon to salon. Their support, trust, and friendship have humbled me in ways I can't explain. Without them, I never would have been able to start my own business. To them, our relationship has gone beyond friendship; it feels like I have an extended family. To those who know who they are, I am eternally grateful for their love and support.

Yet, even these relationships have a strange dynamic. As close as we become, we are only close in the salon. After the appointment, nothing is invested, and nothing is expected. Intense when we're together, and no contact when we’re not. I don’t know of any other relationship that works this way, but it doesn’t inhibit our ability to open up. If anything, it gives us more impetus to share in the time we have. There’s a genuine emotional connection under a time constraint. The exchange between clients and hairdressers is the very fabric of good mental health, and yet we are often oblivious to the ritual we're participating in. Everyone, good or bad, has a story about their hairdresser.

If you’re a hairdresser reading this, working in a salon, your true dedication to your art may never be fully realised. Perhaps you’ll step out for a quick cigarette between clients and see the latest ad campaign for Chanel splashed on the side of a bus. An emaciated model stares back at you, her hair looking like it was styled by a blind person. "I could do that," you'll think, and the truth is, you could—ten times over. The stylist who did that model’s hair was paid ten times more than you are, more than you’ll ever know. But know this: they could never run a column like yours. Never.

Cuts and Confessions

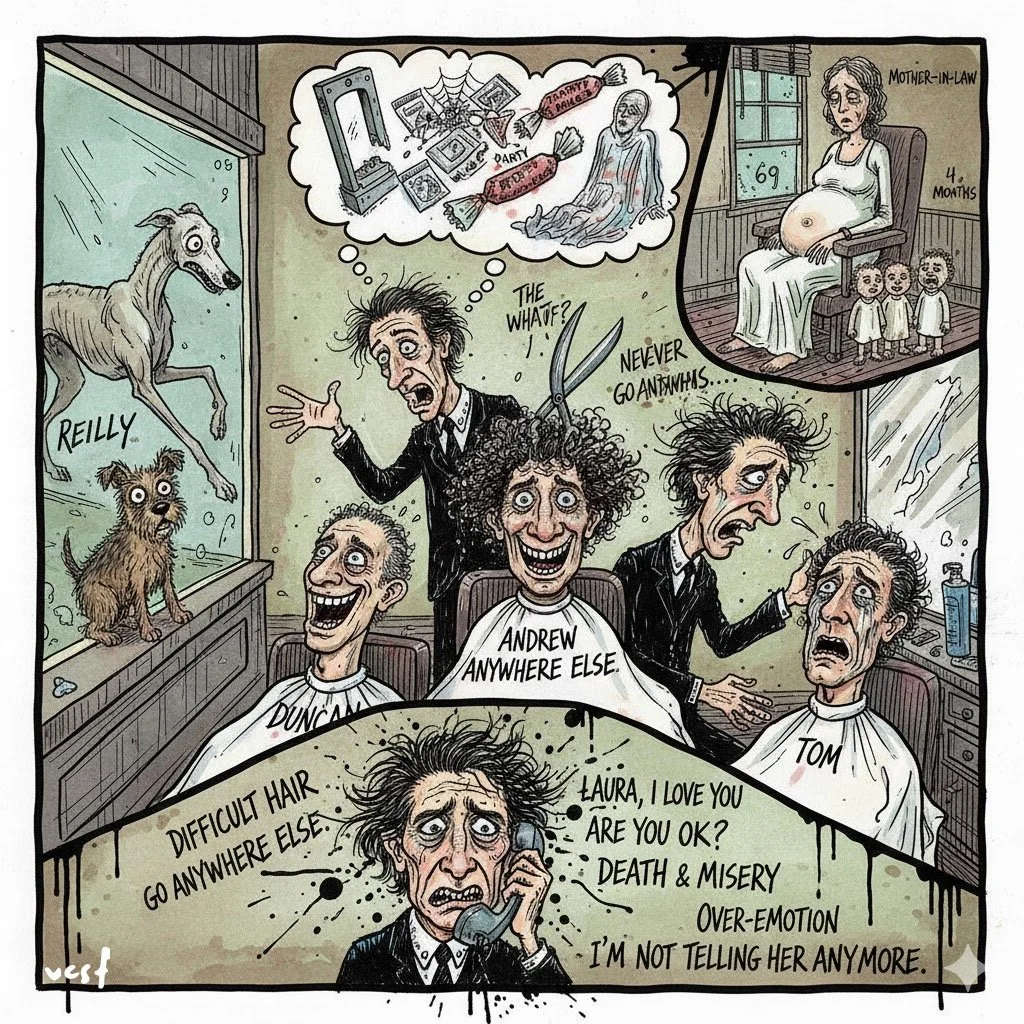

My 9:30 client is late, and even though it's only 15 minutes, it feels like a monumental setback. I know I’ll spend the rest of the day scrambling to make up the time. I can't get mad, though. He's a new dad, probably running on no sleep. I'll just smile, pretend it's no big deal, and get on with it. After all, my time is his time, right?

But his tardiness has a ripple effect. Now I'm late for my next client, a woman in her late fifties. Our monthly appointments are one of her few social outlets. Her life is a little grey, and she comes to me for a bit of sunshine. She talks endlessly about her job, her difficult family, and her unresolved past. I listen, nod, and occasionally ask a question, all while trying not to lose my mind. Our conversations feel like a one-way street; she unloads her burdens, and I soak it all in. I've learned that a lot of my job isn’t just about styling hair—it's about being an emotional punching bag. And I'm getting paid for it, so I guess that's the trade-off.

I became a hairdresser by chance, and it's been a wild ride. I've worked in everything from high-end luxury salons to small backstreet shops. I've met wonderful people and, frankly, some of the most difficult. We stylists are expected to perform miracles in a limited amount of time, not only creatively but emotionally. We're a sounding board for our clients' views and frustrations, even if we don't agree.

Running my own business has changed the dynamic. I have to care about my clients because my livelihood depends on them. But it's hard when I can't relate to them. My salon is in an affluent part of London, and I often feel disconnected from the people I serve. They complain about prices, as if my skill and time are worth nothing. I’ve had to bite my tongue to keep from yelling, “Go somewhere else if you want cheap!” I've listened to them talk about six-thousand-pound fridges and private jet trips, all while they lecture me about social issues. It's a world away from my own, and it can feel like I'm propping up their self-centred reality for a pay check.

I often feel dirty and used, taking money from the very people I resent. I want to tell them what I really think, but I know they wouldn't care. They’d just find a new salon. So I'm trapped in this world of my own making.

I hope that my voice speaks for the hard-working stylists out there. I hope in some way all my bitterness about the injustice of this industry, helps some of you. I hope that you can find something in this book that speaks to you, makes you feel like there is someone else out there who’s made all the mistakes, who’s been a failure and yet in the end it can somehow come good.

This book is a gentle nod of respect to the thousands of stylists out here in every corner of the country working like dogs performing miracle after miracle on every waiting client that comes into see them, one after the other, day after day, week after week, month after month. These are the best hairdressers, and I salute you, your dedication to your art will never be truly realised.

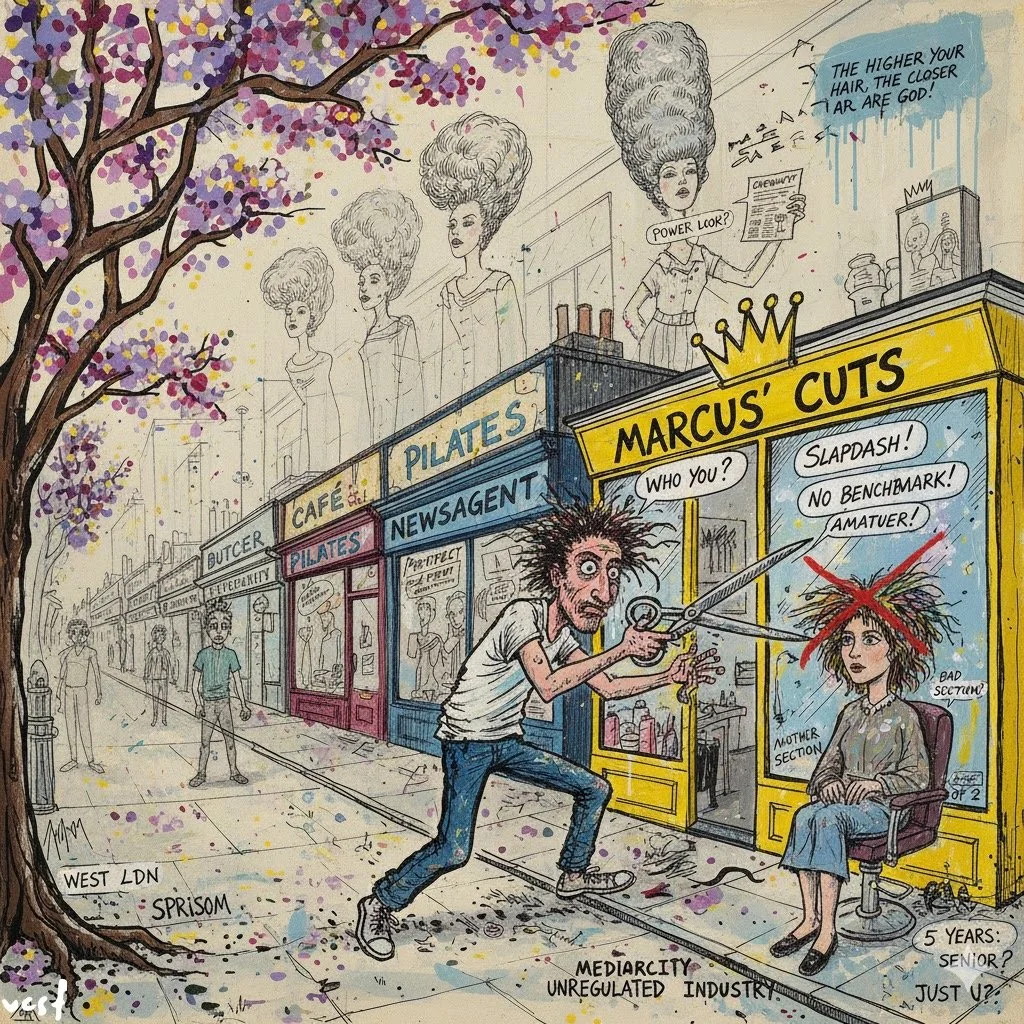

The Great Haircut Heist: How Mediocrity Stole the Value of Artistry Part One.

As an experienced hairdresser with many years in the industry, l've encountered a recurring challenge: clients often have unrealistic expectations when it comes to the value of our services. This issue is not just about the final look they desire but also about the price they expect to pay for it.

Many clients seem to believe that cutting hair is a simple task that requires minimal skill. This misconception couldn't be further from the truth. Hairdressing is an art form that demands a high level of expertise, precision, and creativity. Each client has unique hair types, textures, and preferences, which means that a one-size-fits-all approach simply doesn't work.It takes years of training and experience to master the techniques needed to deliver a personalised and flawless haircut.

Despite this, there is a palpable expectation for hairdressers to reduce their prices. Clients often compare our services to cheaper alternatives, not realising the significant difference in quality and skill. A professional haircut is not just about trimming the ends; it's about understanding the client's vision, assessing their hair's condition, and executing a style that enhances their overall appearance. This level of service requires time, effort, and a deep understanding of hair dynamics. Moreover, the tools and products we use are of professional grade, ensuring the best results for our clients. these come at a cost, which is factored into our pricing. When clients expect lower prices, they inadvertently devalue the expertise and resources that go into providing top-notch hairdressing services.

It's essential for clients to recognise that a professional haircut is an investment in their appearance and confidence. By choosing an experienced hairdresser, they are not just paying for a haircut; they are paying for the years of training, the quality of service, and the assurance of a style that suits them perfectly.

In conclusion, the value of hairdressing services should be appreciated for the skill, dedication, and artistry involved. As hairdressers, we strive to meet our clients' expectations, but it's equally important for clients to understand and respect the value of our work.

The Great Haircut Heist: How Mediocrity Stole the Value of Artistry Part Two.

The air in the salon is thick with the sweet, chemical scent of fresh colour and the sharp tang of hairspray. The rhythmic snip-snip of scissors is a steady metronome in the background, a sound that, to a master, is as deliberate and meaningful as a sculptor's chisel against marble. A true artist in this space understands the quiet language of a client's hair the subtle differences in texture, the unique way it falls, the potential hidden within its fibers. They invest not just in a chair and a pair of shears, but in years of education, in advanced courses, in the relentless pursuit of perfection.

And yet, this mastery is a gilded cage. The industry, as a whole, is drowning in a sea of mediocrity. A quick, weekend course, a social media post, and a discount can now pass for expertise. The barrier to entry has crumbled, replaced by a low-cost, high-volume model that churns out passable haircuts and unremarkable colour jobs. This over-saturation of the average has poisoned the well. Clients, conditioned by the ubiquity of "good enough" and cheap deals, have lost their ability to distinguish true artistry from a basic service. The collective perception of the hair stylist has been reduced from a skilled artisan to a glorified cutter, and the value of their time, their experience, and their art has plummeted.

The most talented professionals are caught in a painful paradox. They are told they can't charge for what they are truly worth because clients won't pay. But it is not the client's fault. How can a patron be expected to understand the difference between a meticulously crafted balayage that wit grow out seamlessly and a rushed, foil-heavy dye job that will leave them with stripes a month later? The industry has failed to educate its own. It has not established clear standards, celebrated its masters, or created a pathway to excellence that is both visible and valuable to the public. It has instead prioritized speed and volume, leaving a trail of indistinguishable, lacklustre work in its wake.

The most damning truth is the absence of a unified, regulatory board. There is no central body to demand a minimum standard of expertise or to prevent the industry from becoming a free-for-all. This lack of oversight has turned the hairdressing world into a sort of Wild West, where anyone with a pair of scissors and a business license can open a salon, regardless of their skill or experience.

The market is flooded with practitioners who compete solely on price, further eroding the value of the true craft. This is not the fault of the public, but the failing of an industry that has no mechanism to protect its standards, and therefore no defence against those who are content with doing the bare minimum.

This is a crisis of value, not a failure of the market. The problem is not that society refuses to pay for skill; it is that the hair industry has made skill invisible. It has failed to create a system that elevates and protects its best and brightest, and in doing so, it has allowed the art of hair to be devalued by the very people who practice it. The true artist, with their hands, their heart, and their expertise, is left to fight a lonely battle against a tide of mediocrity that their own profession has enabled.

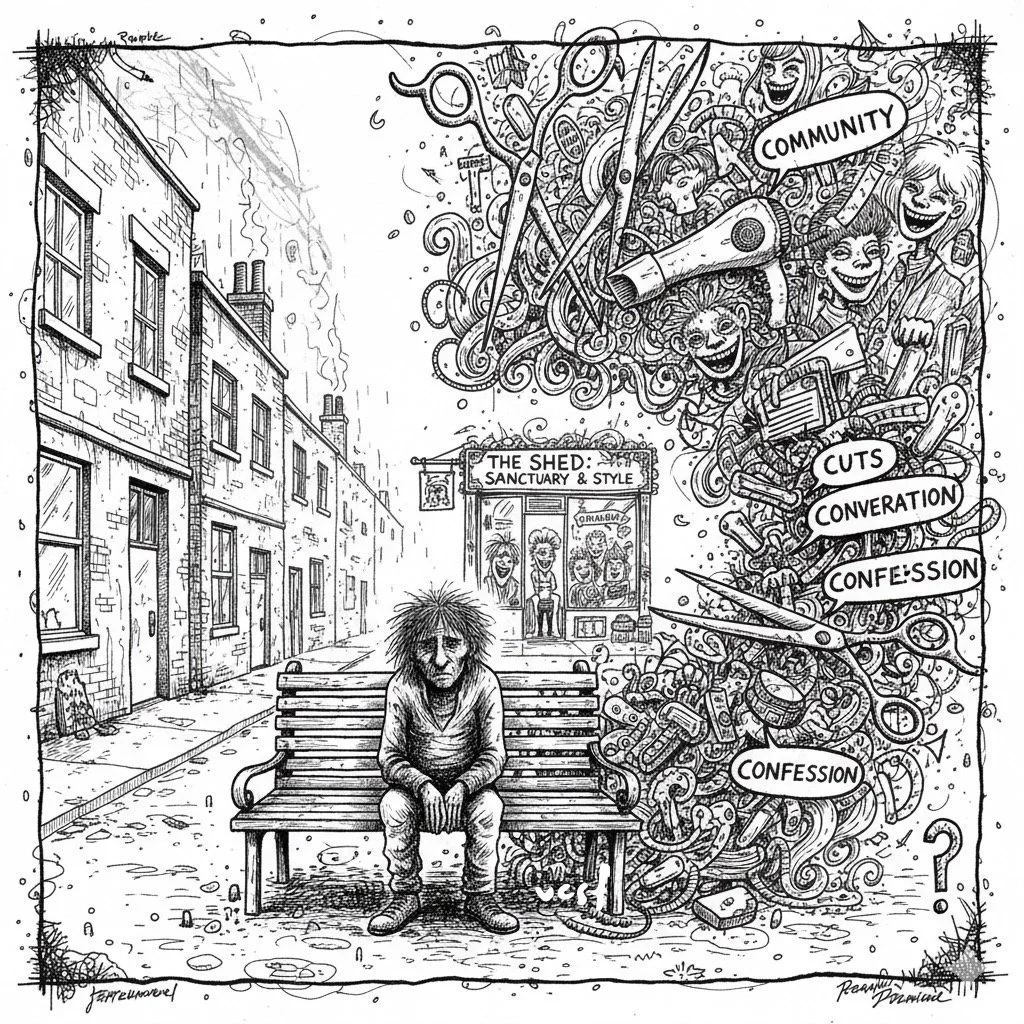

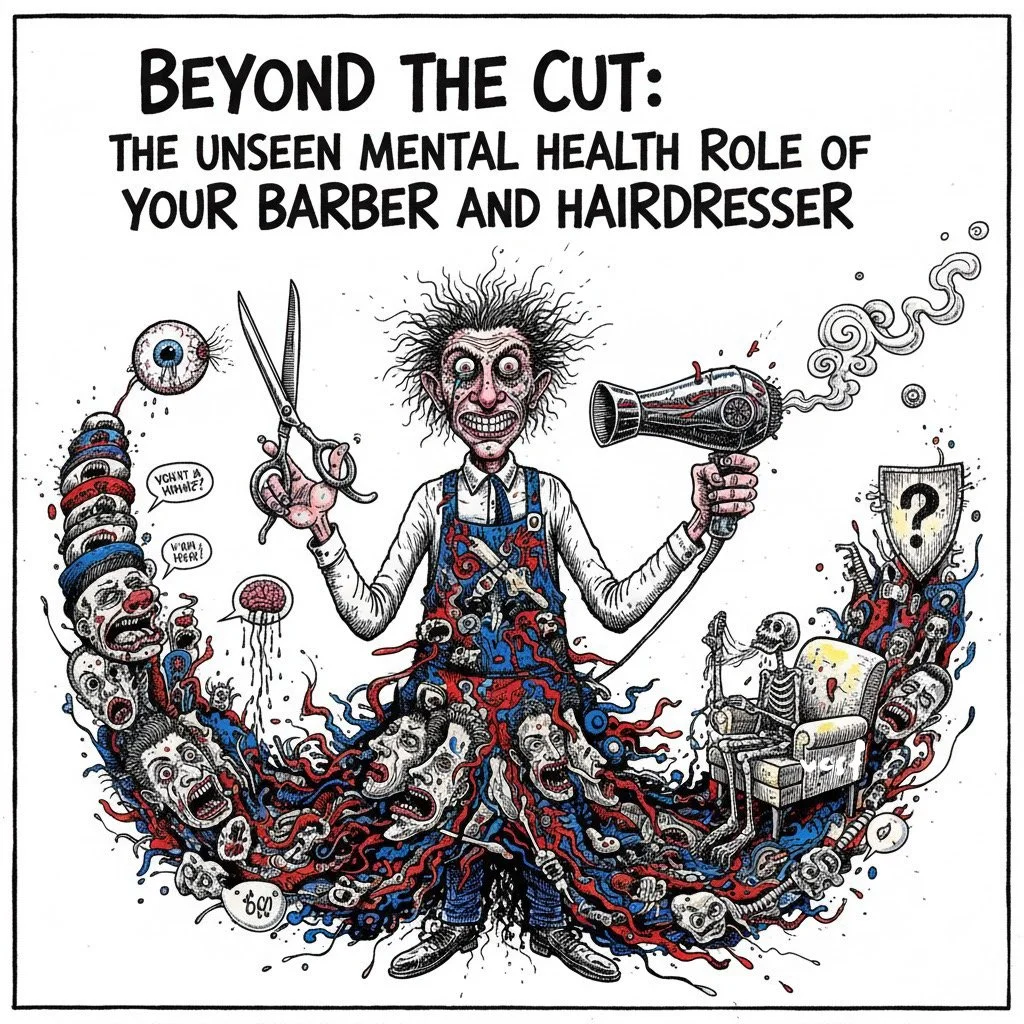

The Unsung Role of Hairdressers in Combating Loneliness

The UK government's Tackling Loneliness Network was formed in response to the growing issue of loneliness, which was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The network, which includes over 70 organizations from various sectors, operates on the principle that a collaborative, whole-society approach is essential to addressing loneliness. Its vision is to be a "partnership of equals," with each member contributing their unique expertise, knowledge, and community connections to a shared goal.

The network focuses on four key areas:

Tackling loneliness in young people: This acknowledges that loneliness is not exclusive to the elderly.

Tackling loneliness in older people: A traditional focus of loneliness initiatives.

Local and place-based approaches: Recognising that solutions must be tailored to specific communities.

Digital inclusion: Addressing the role of technology in both causing and alleviating loneliness.

Loneliness is a deeply personal and pervasive issue, and its impact on mental and physical well-being has been formally recognised by governments, including the UK, which appointed a Minister for Loneliness in 2018. This was a response not only to the COVID-19 pandemic but also to the broader understanding that a significant portion of the population felt lonely and isolated long before lockdowns began. The government's strategy involves working with a diverse network of organizations to reduce the stigma associated with loneliness and to help people reconnect.

A key part of this strategy is signposting, where individuals are directed to resources and support. A total of £34 million was allocated to projects aimed at tackling loneliness, with a significant portion dedicated to this effort. Healthcare workers, for example, are being trained to spot the signs of loneliness and offer help. The idea is that everyday interactions—from a visit to the GP to a trip to the local shop—can serve as opportunities to make a difference.

However, a surprising omission from this extensive network is the hairdressing industry. In a list of over 40 organizations, including media giants, hospitality chains, and charities, there is no mention of hair salons, barbershops, or any related professional bodies like the National Federation of Hairdressers and Barbers (NFHB). This is a glaring oversight.

As a hairdresser with 25 years of experience, I am uniquely positioned to address the issue of loneliness. Unlike many other professions, hairdressers spend sustained, regular periods of time with clients in a non-judgmental, tactile, and personal setting. They serve as a constant presence in their clients' lives, often listening to their problems, sharing in their joys, and providing a sense of connection that may be lacking elsewhere.

This is more than just a job; it's a vital community service. Hairdressers often act as informal therapists, carrying the weight of their clients' emotional burdens—from personal challenges and difficult emotions to deep-seated feelings of loneliness and isolation. For many, a monthly salon appointment is one of their few avenues for social contact outside of work.

I argue that the government is overlooking an obvious and powerful solution by not including the hairdressing industry in its strategy. Hairdressers are already doing the work of the Tackling Loneliness Network, serving as a frontline for community well-being. By ignoring this profession, the government misses a crucial opportunity to leverage an existing infrastructure of compassionate, empathetic, and dedicated individuals who are already making a difference every single day.

I believes that the government's approach of "throwing money and re-touching" parts of society that don't see their communities every day is flawed. Instead of starting from scratch, the solution lies in empowering those who are already helping. I propose that hairdressers should be given the proper training and tools to effectively support the people they see daily.

Hairdressers are affectionately called "therapists," and there's a reason for that. By providing them with an understanding of mental health issues and effective communication strategies, we can enhance their ability to help clients navigate their feelings of loneliness. This approach would be more efficient, impactful, and would recognize the invaluable role that hairdressers already play in society. It's a call to action: acknowledge the silent work of hairdressers and give them the resources they need to save the world from loneliness, one haircut at a time.

The Curious Case of Jamie Oliver's Hair

Jamie Oliver is a familiar face on British television, having built a brand around his "mockney" charm and accessible cooking. He's a national treasure known for his culinary activism and business ventures. However, despite his public success, I’m taking a critical look at one particular aspect of his public image: his hair. The stylist who has built a successful career specialty in styling—a word I would emphasise, suggesting it is distinct from the more technical skill of haircutting, has been tasked with the difficult exercise of cutting his hair, an exercise most would find challenging.

The challenges of Jamie Oliver's hair. It's not a straightforward head of hair; it's "slippery." It's fine but dense and grows quickly. The most significant challenge, however, are the two cowlicks above his left eye, which can only be described as "tricky buggers." These issues require advanced training and practice, which I actively pursued to master difficult hair types and hairlines.

Looking at Oliver's hairstyles over the years, I’ve realised he's never really seemed fully comfortable with his hair. Early on, a dishevelled look suited his younger, thinner appearance. As he's aged, his hair has become more difficult to manage Now with.the stylist, lacking the proper cutting skills, has only been able to accommodate Oliver's requests for short, slicked-back styles, which were easier to manage but still looked awkward due to his cowlicks. The result is unflattering. He looks even puffier and more bloated his hair somehow super imposed onto his face.

But the situation has reached breaking point now that Oliver is growing his hair out. I’m reluctantly critical of the results because It's not the stylist’s fault. This is just another example of an underqualified individual profiting from a lack of high-level skill, a problem which is endemic in the industry. I’m frustrated. While I’ve dedicated my career to mastering the difficult art of haircutting, a "substandard" result is being showcased on national television, garnering thousands of pounds in pay.

Jamie Oliver is a "brilliant personality," but his hair has reached an impasse.

Ps. Jamie had recently had his haircut. It made the national news. It wasn’t by me, but I coined it months before it needed to happen. I could have done a better job.

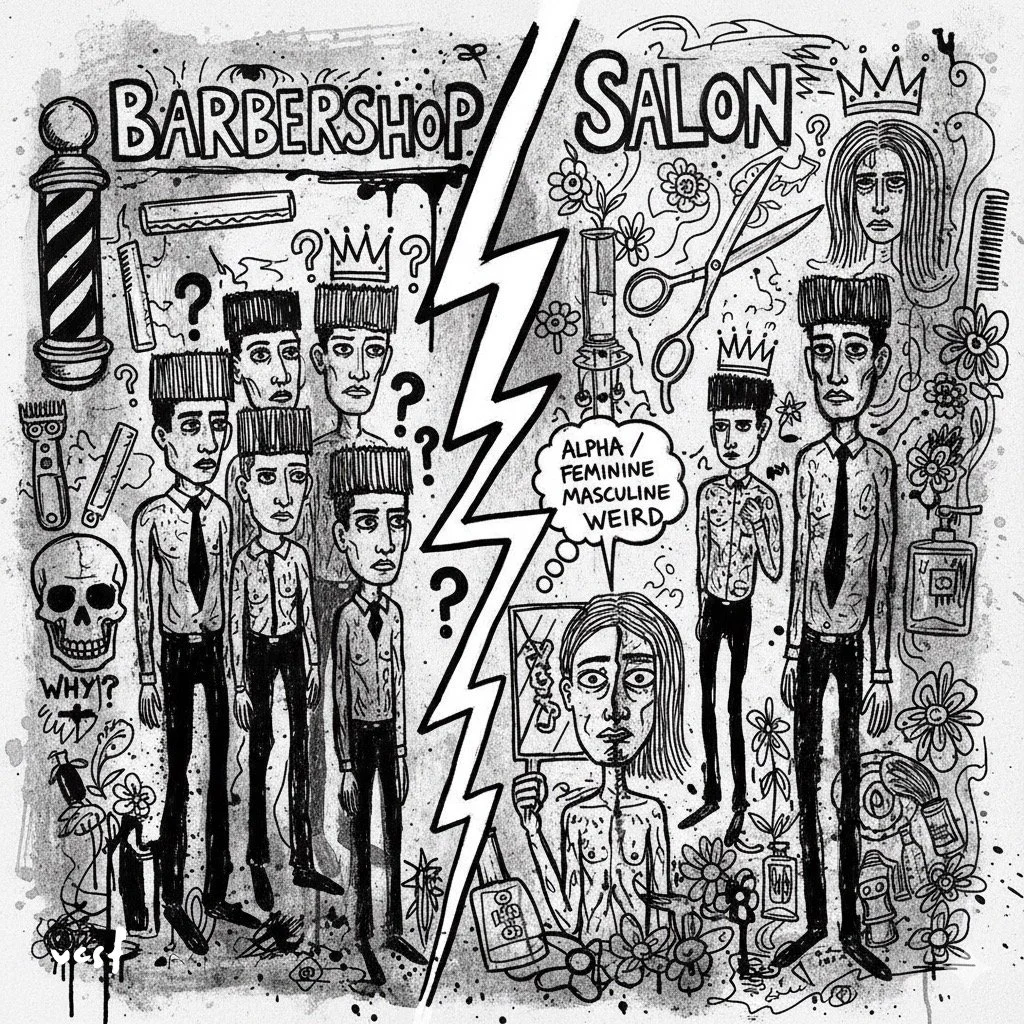

Barbershops vs. Salons; The Barbershop Performance, Precision Beyond the Clipper, The Bespoke Silhouette and The Hypocrisy of Alpha.

Walk into a modern barbershop, and you’re met with an air of deliberate, almost aggressive, ruggedness: reclaimed wood, dim lighting, often a skull or a vintage motorbike accessory in the corner. They’re selling a performance of manhood—straight-up, no-nonsense. The barbershop often feeds an acceptable version of masculinity, an enclosed space where you must perform. You can’t be seen as too soft, too interested in aesthetics. But secretly, they’re still getting their fades and their beard line-ups done with the same attention to detail we offer in the salon; they’re just doing it under the guise of an "edgy" or "traditional" setting.

That's where the false masculinity really comes into play. It’s less about hair and more about a calculated image. It’s an odd dichotomy, the whole thing with barbershops versus salons. Honestly, it's about the performance of masculinity. Their approach is all about the stoic man-to-man exchange. They’re selling the idea that their establishment is where real men go for a haircut—a space free of the 'fuss' they associate with a salon.

In the salon, my space, it's all about comfort, about me making you feel good. When the blokes from the building sites or the boxing gym come in—the geezer types—they’re the most open. They're the first to compliment me. "You smell lovely, mate. Is that Issey Miyake?" They're tactile, they air-kiss, they talk about my clothes. They’re the ones who go on about being alpha male; they think their unquestioned straightness means they can be cuddly, even a bit... feminine in their appreciation of style. It’s an easy-going, if sometimes baffling, confidence.

The difference isn't the haircut; it's the courage to be vulnerable, or at least, the lack thereof. In the salon, we embrace the scent of Issey Miyake; in the barbershop, they’re still trying to mask their interest in it.

In terms of the work Forget the loud, buzzing simplicity of the barbershop. What happens in my chair is an entirely different discipline—it’s where dexterity meets true design.

Most men who flock to the barbershop have that ubiquitous, thick, easy hair—the kind that takes a clipper to a Number 2 fade and calls it a day. That’s a nominal cut, a cost-effective choice because, frankly, it’s largely devoid of any real skill. The clipper does the heavy lifting, relying on the client's dense, forgiving hair to mask any lack of finesse.

My male clientele, the ones who can't go to the barbers, come to me for a reason: their hair demands respect. They might have hair that's fine, thin, curly, or wildly unpredictable, often with tricky growth patterns or cowlicks that threaten to ruin the silhouette.

This is where the sheer dexterity of my training comes into play. It's an intimate, fluid dance with the strands. It starts with the scissor-over-comb technique, a rhythmic, almost meditative action that requires an entirely different level of precision than a guard-on-clipper cut.

The scissor work, I'm not just cutting length; I’m building internal structure. My hand positioning is constantly adapting, pivoting the comb—my temporary guide—and working the shears with minimal movement to achieve soft, seamless transitions that clippers simply can't replicate. It's the difference between blending paint with a roller and blending it with a fine brush. My texturizing and weight distribution is the invisible skill. With a flick of the wrist and specialized shears, I meticulously manage the hair's weight and density. I use point cutting to soften the ends, preventing that blunt, helmet-like look, and techniques like slide cutting to encourage movement and flow. This subtle work ensures the style looks fantastic when dry and falls perfectly into place with minimal product.

The goal isn't just a short haircut; it’s a bespoke silhouette.

A barber's uniform approach is a template; my work is a tailored suit. I am cutting to enhance cheekbones, disguise a receding hairline, or give volume where there is none. This is why the service commands a higher price—it’s not for the time, but for the cumulative years of skill that allow me to see the finished shape before the first strand is cut.

In short, I'm handling hair that tells the truth. It’s hair that requires skilful, manual graduation and an acute eye for detail. When these men leave my salon, they have a haircut that is as sophisticated and individual as they are, a style achieved through a precision that is worlds away from the buzz of a basic clipper cut.

That's where the false masculinity really comes into play. It’s less about hair and more about a calculated image. It’s an odd dichotomy, the whole thing with barbershops versus salons. Honestly, it's about the performance of masculinity. Their approach is all about the stoic man-to-man exchange. They’re selling the idea that their establishment is where real men go for a haircut—a space free of the 'fuss' they associate with a salon.

In the salon, my space, it's all about comfort, about me making you feel good. When the blokes from the building sites or the boxing gym come in—the geezer types—they’re the most open. They're the first to compliment me. "You smell lovely, mate. Is that Issey Miyake?" They're tactile, they air-kiss, they talk about my clothes. They’re the ones who go on about being alpha male; they think their unquestioned straightness means they can be cuddly, even a bit... feminine in their appreciation of style. It’s an easy-going, if sometimes baffling, confidence.

The difference isn't the haircut; it's the courage to be vulnerable, or at least, the lack thereof. In the salon, we embrace the scent of Issey Miyake; in the barbershop, they’re still trying to mask their interest in it.

In terms of the work Forget the loud, buzzing simplicity of the barbershop. What happens in my chair is an entirely different discipline—it’s where dexterity meets true design.

Most men who flock to the barbershop have that ubiquitous, thick, easy hair—the kind that takes a clipper to a Number 2 fade and calls it a day. That’s a nominal cut, a cost-effective choice because, frankly, it’s largely devoid of any real skill. The clipper does the heavy lifting, relying on the client's dense, forgiving hair to mask any lack of finesse.

My male clientele, the ones who can't go to the barbers, come to me for a reason: their hair demands respect. They might have hair that's fine, thin, curly, or wildly unpredictable, often with tricky growth patterns or cowlicks that threaten to ruin the silhouette.

This is where the sheer dexterity of my training comes into play. It's an intimate, fluid dance with the strands. It starts with the scissor-over-comb technique, a rhythmic, almost meditative action that requires an entirely different level of precision than a guard-on-clipper cut.

The scissor work, I'm not just cutting length; I’m building internal structure. My hand positioning is constantly adapting, pivoting the comb—my temporary guide—and working the shears with minimal movement to achieve soft, seamless transitions that clippers simply can't replicate. It's the difference between blending paint with a roller and blending it with a fine brush. My texturizing and weight distribution is the invisible skill. With a flick of the wrist and specialized shears, I meticulously manage the hair's weight and density. I use point cutting to soften the ends, preventing that blunt, helmet-like look, and techniques like slide cutting to encourage movement and flow. This subtle work ensures the style looks fantastic when dry and falls perfectly into place with minimal product.

The goal isn't just a short haircut; it’s a bespoke silhouette.

A barber's uniform approach is a template; my work is a tailored suit. I am cutting to enhance cheekbones, disguise a receding hairline, or give volume where there is none. This is why the service commands a higher price—it’s not for the time, but for the cumulative years of skill that allow me to see the finished shape before the first strand is cut.

In short, I'm handling hair that tells the truth. It’s hair that requires skilful, manual graduation and an acute eye for detail. When these men leave my salon, they have a haircut that is as sophisticated and individual as they are, a style achieved through a precision that is worlds away from the buzz of a basic clipper cut.

A Home Hairdressing Visit: A Brief Account of the Complexities of Pricing in Personal Hairdressing Services

A hairdresser arrived at the elegant home of a wealthy client, summoned to provide haircuts for the client and her two eleven-year-old children. The atmosphere was comfortable and familiar, but the practicalities of the profession remained ever-present. After setting up his tools in the sunlit living room, the hairdresser began with the client herself, crafting a precise cut tailored to her taste. The children were next, lively and wriggling in their seats, each requiring patience and skill to coax into stillness and ensure a stylish, even cut. Once the work was complete and the last strands had been swept away, the client prepared to pay. At this point, she raised an objection, her tone edged with disbelief. She questioned why she was being charged as much for her children’s haircuts as she was for her own, especially since, in her mind, children’s hair should cost less. This led to a candid discussion about the difficulty in pricing such personal services. For the hairdresser, the time, effort, and professional expertise required for a child’s haircut often match, or even surpass, those for an adult. Children can be restless or anxious, needing special reassurance and careful handling, which can make the task intricate and demanding. The hairdresser explained that, as a result, a child’s haircut is priced the same as an adult’s. Each service reflects not just the time spent, but the skill and adaptability involved qualities that don’t diminish simply because the client is young. Despite her wealth and her habitual expectation of preferential treatment, the client left the conversation with a new appreciation for the complexities behind the cost, even if she remained unconvinced about the final total on her bill.

‘He pulled his worn leather bag of shears, combs, and colour tubes out of his beaten-up bag. He was a home-visiting hairdresser in the affluent suburbs, a profession that, on the surface, seemed straightforward. You set your price, cover your costs, and earn a living. Yet, like the women who sought his services, the pricing in personal hairdressing services was anything but simple—it was a tangle of invisible factors, emotional needs, and economic realities.

His pricing model was a chaotic masterpiece reflecting these complexities: product cost, travel time, experience, location, and rent/utilities all went into the calculation. But then there was the unwritten complexity: the emotional fee.

Most of his clients were married women, comfortably settled in lives of financial freedom provided by their husbands. These were homes of manicured lawns and loveless marriages, where the air was thick with a thirst for nourishment that no amount of material luxury could quench. The husbands were often distant, overweight, and devoid of any real understanding about their roles—a backdrop of comfortable neglect. It should be so much simpler. It was a simple transaction. He dreams of transactional. But these women came to adore, worship, and want him, some without ever truly admitting the depth of their desire, an invisible intensity that had vanished from their married lives. They didn't realise that what they misunderstood, what nobody understood, is that it’s just the job, the job of a hairdresser.

He was staring at his ceiling fan, the gentle, hypnotic whir the only thing holding the room's disparate noises at bay. He was tired. The exhaustion was a deep, bone-weary ache that wasn't just physical; it was the residue of countless hours spent in the intimacy of others' homes, absorbing their silences, their needs, their unarticulated cravings. He closed his eyes. The room was fading. The ceiling fan blades were warping, becoming a slow, spiralling vortex of tired grey. A fugue-like state was washing over him, a numb detachment from the clippers still sitting on his kitchen table, the scent of peroxide faintly clinging to his jacket. The drone of the fan morphed into the low thrum of a high-end sound system, the kind that whispers classical music in a waiting room. The walls around him materialised, no longer the paint-peeling rental he knew, but the polished, reassuring wood panels of a psychiatrist's office.

A screen on the wall flickered to life, showing a familiar scene, a transcript playing out in stark, white text against the blue glow, The sopranos, Tony wrestling with his own complicated feelings for a woman who held his vulnerability in her hands.

Her voice was cool, measured, intellectually sharp—the voice of Dr. Melfi, wasn't talking to Tony anymore; it was talking directly to him, talking as if she was communicating through him to his client.

‘I know this maybe very hard for you to swallow. But you’re only feeling this way because we’ve made such progress. I’ve been gentle. That’s my job. I listen. That’s what I do best.

The words echoed in the enclosed space of his dreaming mind, resonating with the very core of his profession. I've been gentle. That's my job. He saw his own hands, his tools, his curse.

Again, she spoke ‘I’ve been a broad sympathetic generic woman to you because that’s what this job calls for. You’ve made me all the things that are missing in your life. And in your marriage.,.

You’ve made me all the things that are missing... he felt a cold dread. That was it, the truth of the complexity of hairdressing. The price wasn't just for the skill; the surcharge was for the emotional labour, the act of being the nourishment these women, starved in their financially free cages, so desperately sought. He was the empty space they filled. The sympathetic ear. The gentle touch. The one who made them feel wanted. The one they mistakenly thought loved them and he resented it.

‘I’ve been gentle. That’s my job. I listen. That’s what I do best.’

Her words repeated, a mechanical mantra, stripping the romance from his accidental affairs, revealing the stark, transactional nature beneath. His attention wasn't desire; it was customer service. His intimacy was the unspoken, highly valued component of his expertise. He was professionally intimate and tragically empty. He was providing a life-affirming emotional illusion, and they were paying him handsomely for it.

He opened his eyes. The ceiling fan was still there, the blur slowing down. The fugue was lifting, but the cold clarity remained: created an illusion of love and singular connection. This intensity was just an essential part of the high-touch, personal service he provided, necessary to build the trust that kept him booked solid.

Consultations of the rich and famous.

Dear Cathy,

I'm a senior hairdresser with twenty years of experience, now running my own private salon in West London. My client, Dorothy Byrne, suggested I write to you to provide a hair consultation, which is an unusual but welcome challenge for me.

The normal consultation process is an in-person exchange where I assess a client's hair, listen to their history, and understand their personality and style goals. Because I can't meet you, I will instead offer my professional opinion, what I would propose to do, and how I would do it.

From what I can see, your current graduated bob, while structured, lacks movement and doesn't fully flatter your features. The style is a common choice for your hair type due to its density, but its rigidity can make the hair look motionless and unattached to you. In my experience, this is often the reason stylists keep the shape the same over the years.

I believe your hair can do more for you. I propose a complete restyle with the goal of creating a younger, more flattering, and feminine look that aligns with your style. I would make it shorter in certain areas to emphasize the natural shape of your head and would ensure that the roots sit flat to the scalp, which I believe is the key to a successful restyle for your hair type.

The core of the haircut would be a shorter, graduated shape at the back, but I would also open up the sides to reveal your ears and highlight your cheekbones. The front would be softened to complement your bone structure, while the parting would remain the same for your comfort. My unique approach to cutting involves carving and distributing the hair's weight without using thinning scissors, ensuring the final result is soft, subtle, and balanced.

I understand this requires a significant leap of faith, as I cannot offer you reference images. The style I envision would be completely bespoke, tailored to your head shape, features, and hair type. I have the confidence and skill to create a short, feminine, and flattering cut that will change your look for the better.

As I work alone in my salon, the appointment would be private, without the distractions of other stylists or clients. This would allow me to take as much time as needed to properly execute the restyle, ensuring you feel confident in what I have done and that I can support you in maintaining the style in the future.

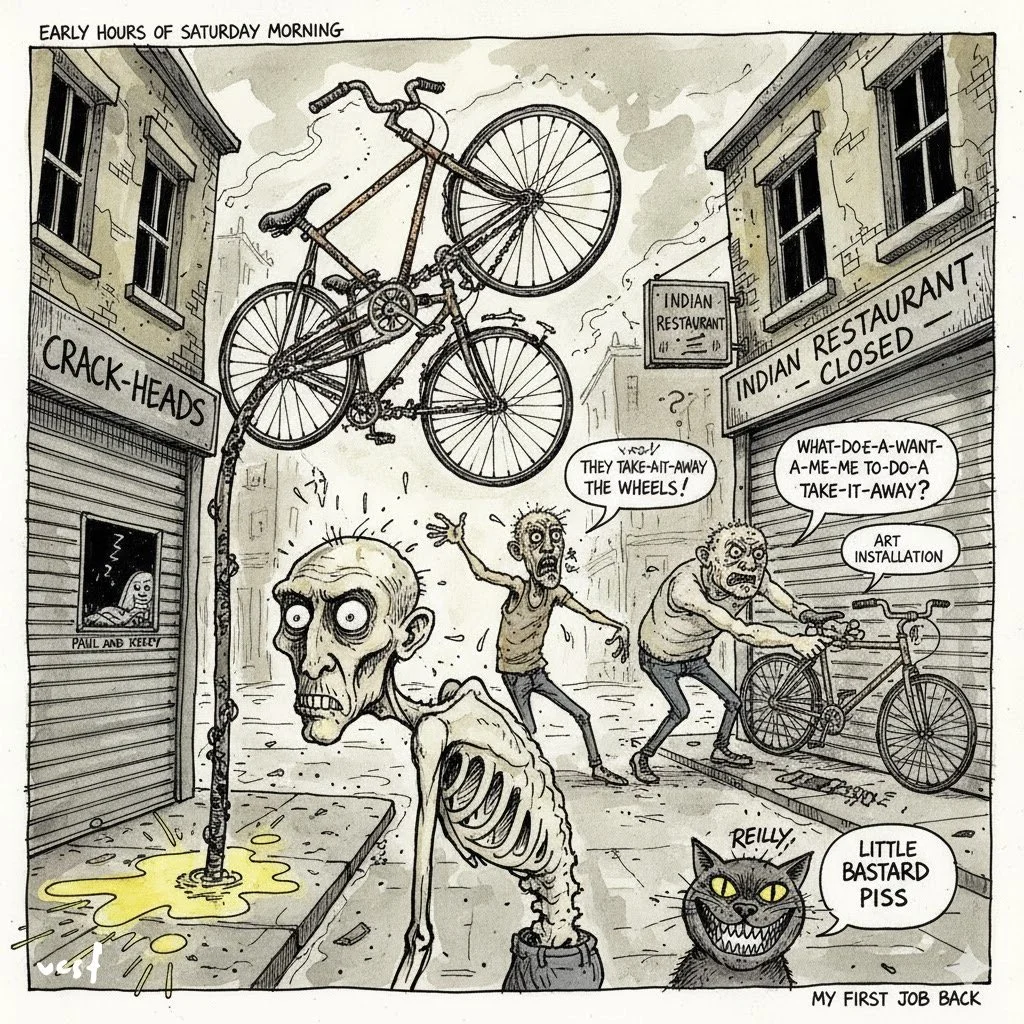

Born Performer, Found Profession: My Escape to the Hairdressing Life

In the beginning, my life was anything but the calm of a wealthy West London enclave. I started at the bottom, in the unglamorous world of small-town Scotland, a place I had moved to after a turbulent boarding school experience. In Crieff, a small town in the heart of the Trossachs, my English background made me a target. I was the odd one out, an outsider in a world of fourteen-year-old alcoholics and misfits who saw me as an easy target. One evening, after a night out with a friend, a fight broke out at the local disco. My friend was struck with a pool cue, and in the ensuing chaos, I was sucker-punched by someone I had just moments before seen as an ally. This environment of casual violence and constant threat was the reason I wanted out.

With no clear plan, I enrolled in an acting course at Falkirk College. My only goal was to secure a student loan and escape. The course was a motley crew of dropouts and social outcasts, led by a group of equally jaded, soon-to-be-retired tutors. I had no interest in becoming an actor, but I was a natural performer. My entire life had been a performance—I was a chameleon, constantly adapting to fit in, using humour and charisma to make people like me. My need to be wanted, a deep-seated desire born from a neglected childhood, was a powerful motivator.

It was this very need that led me to my first salon in Glasgow. It was a city that, to my surprise, felt like home. My Scottish mother’s heritage suddenly felt real, a connection I’d never known. My first salon, run by a husband and wife, felt like the family I had always craved. Salons, for all their clichés, truly are like families—a blend of oddballs, outcasts, and gregarious personalities all working together. It was an inclusive, egalitarian environment that welcomed everyone regardless of their background.

My days as a salon assistant were a gruelling blur of twelve-hour shifts. I cleaned, swept, and smiled until my face hurt. It was a physically and mentally demanding job, but I was captivated. I watched the stylists like an artist in awe, mesmerized by their swagger and skill. They were the coolest people I had ever met, effortlessly sculpting hair with a level of detail and artistry that I found breathtaking.

I learned the unspoken rules of the salon family. A culture of tipping and mutual support existed beneath the surface. I saw stylists discreetly slip cash to assistants who helped them, a fair system based on loyalty and hard work. But I also saw the immense power stylists wielded. A single stylist could cripple a salon by leaving and taking their clients with them, a fact I witnessed firsthand when two top stylists left a major London salon, taking hundreds of clients with them.

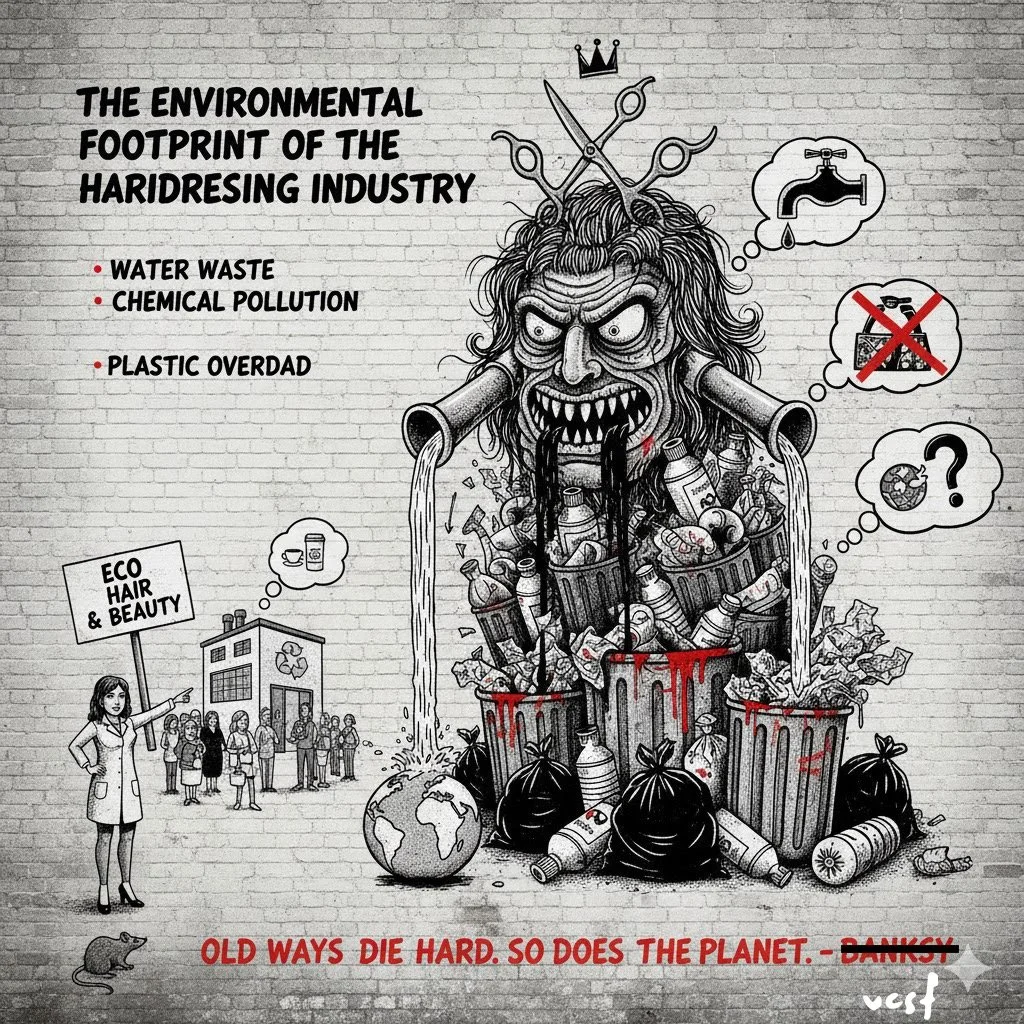

Washing Away Sustainability: Confronting the Hairdressing Industry's Environmental Footprint

The hairdressing industry, a global service that billions of people use regularly, has a significant and often overlooked impact on the environment. From water and energy consumption to chemical waste, many of the day-to-day practices in salons are detrimental to ecological health. For decades, these practices have remained largely unchanged, with the burden of innovation often falling on small, independent salons rather than large, corporate chains.

A 2018 study by the University of Southampton highlighted this issue, noting the general lack of engagement from hairdressers when asked about their environmental impact. In response, Denise Baden, one of the study's leaders, founded Eco Hair and Beauty, an organization dedicated to empowering hairdressers to understand their environmental footprint. The organization offers a certification that encourages professionals to adopt more sustainable practices. However, while resources and guidelines for sustainable practices exist, widespread adoption remains a challenge, particularly among larger industry players.

A critical look at the industry reveals several areas where change is both necessary and possible.

One of the most significant sources of waste in salons is the aluminium foil used for highlighting. A single salon can use hundreds of meters of foil each week, a number that becomes staggering when extrapolated across the thousands of hairdressers in a country. The chemicals on the used foil complicate the recycling process, requiring specialized handling. However, dedicated recycling services, such as one in New South Wales, Australia, have started to tackle this problem, demonstrating that with proper systems, this waste can be repurposed rather than sent to a landfill.

Another area ripe for change is the use of disposable plastic bottles for retail products like shampoo and conditioner. Following the example of the coffee industry, which has seen a shift toward reusable cups, hair salons could implement a similar system. Customers could purchase a product in a reusable container and then return to the salon for discounted refills. This model would not only reduce plastic waste but also encourage customer loyalty, as using the same product consistently over a period of three to six months is essential for achieving the best results. While there may be logistical hurdles to overcome, this simple idea has yet to even be seriously discussed within the mainstream industry.

Ultimately, for significant change to occur, the push must come from the top. The major corporations and salon chains that dominate the industry have the power and resources to implement large-scale sustainable practices. As it stands, being "eco-friendly" is still seen as a niche market rather than a necessary standard. The continued use of unsustainable practices causes irreversible damage to the environment. The industry must confront a fundamental question: just because a practice has been done for a long time, does it mean it should continue?

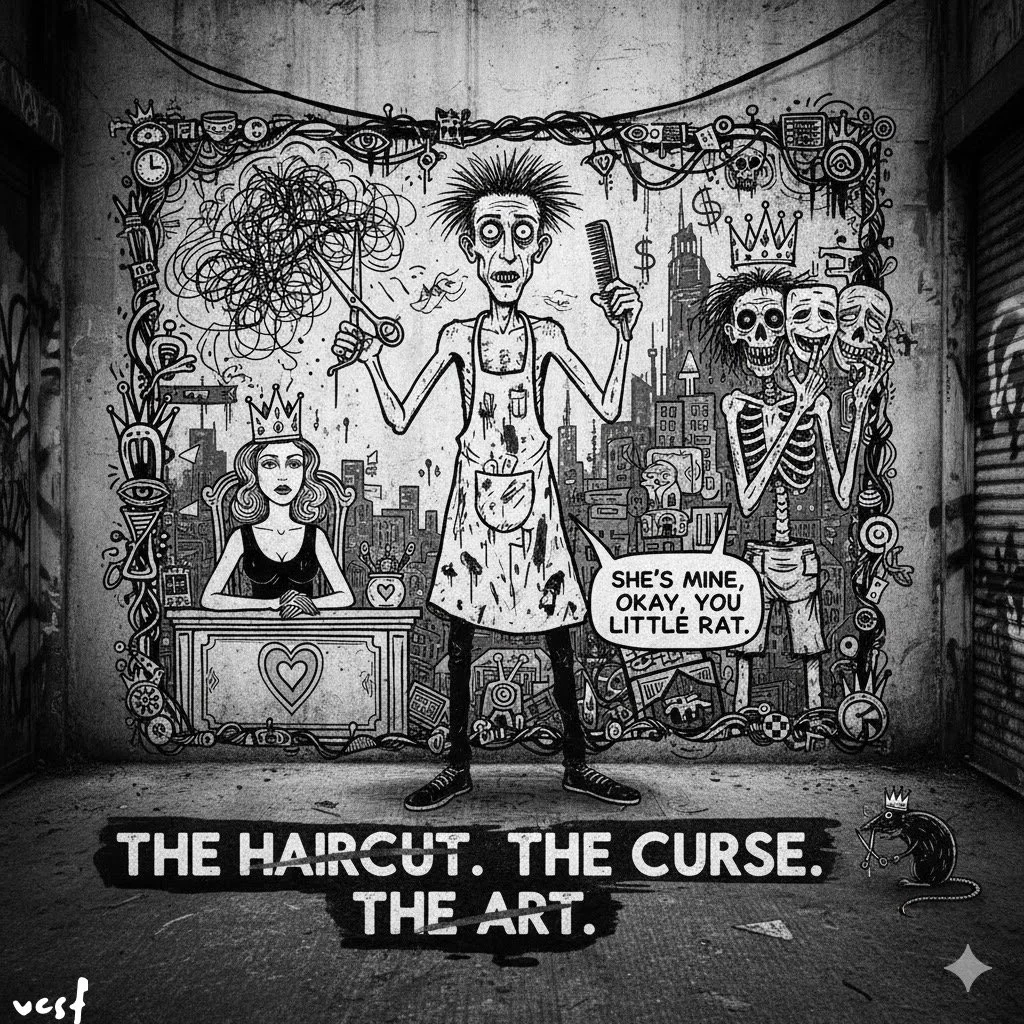

Tales from the underbelly part two

Stuart has been my client since the old days. He’s a photographer, a man who believed if you want to capture true emotion, you have to create it, no matter the cost. His methods were controversial, and for many, he pushed the envelope too far. His last archived image, a warning in the halls of learning, is of a bloodied model’s face—her lips swollen, her wounds disturbingly realistic, and her eyes holding a fear too forbidden to stare at, yet too intriguing to look away. That’s what he wanted: an image so uncomfortable, so unsettling, you couldn't tear yourself from it because it made you feel something. Whatever is said about Stuart, he had his moments, and if nothing else, he always committed to his art.

I think that’s how I justify keeping him as a client. He commits to his art the way I commit to what I do. It’s also possible I feel sorry for him, because I think I feel sorry for myself.

The thing is, I cut his hair better than anyone else. Stuart's hair requires more attention than most; even if I spent half the time I normally do, it would still be 70% better than any other hairdresser out there. His head shape is not kind, either. It’s flat at the back, and the combination of coarse, robust hair and a flat head shape means you must work hard to create movement. Too short, and the hair will stick perpendicular to the scalp, making him look ridiculous. Too long, and he’d look like a Shetland pony, his hair shapeless and heavy. It’s the type of hair that only a seasoned professional can cope with. This would be a nightmare for any other stylist in any salon.

So, I’m stuck with him. My ego and pride won’t allow me to mess it up. The haircut is art, and I could never bring myself to make it anything less than the best I could do. What’s the point of doing it otherwise?

I see Stuart at his studio; it’s easier that way. I don't want him turning up at the salon. The last time he did, he threatened one of my clients. When he's around people who aren't part of his world, his acute anxieties make him outwardly intolerant and aggressive. He's unhinged, a loose cannon. He is like a man who's never met anyone before. On top of that, he is tenacious. He doesn’t take no for an answer. There is no answer but to acquiesce. I find it easier and safer to meet his demands rather than negotiate with him. With Stuart, it’s a curse. I am one of the only people close enough to him to see him for what he is. And what he is, is ugly.

Going to see him at the studio, however, is an excuse to see Melanie, who doesn’t really work with him but somehow manages him. She has a submissiveness about her, a vacant leniency to even his most heinous behaviour which somehow helps him continue to work on a subsidiary level. Whatever is said about Stuart, his taste in women is sublime. Melanie is a woman of striking beauty, her presence captivating.

I get in early to chat with Melanie. She stands behind a large, round, altar-like desk the colour of whale skin. Bright, overly engineered lights fizz off her perfect skin, the shadows bouncing off her structure in the way only a model can. I walk in and she smiles warmly.

“He,” she says, pointing to the large steel door to her right, “is in a right one today.”

Suddenly, the large steel door flies open. The Incredible Hulk has burst through. It startles Melanie. I don't blink. Stuart strides in, wearing a tracksuit. He is a man in his late fifties, the last bastion of free thought, a man without cause, merely aiding his final epitaph.

Melanie stands at attention, a mechanical smile covering her face. He doesn’t even register she’s there. He looks right at her and directs his question to me instead.

“Where have you been?”

Before I can answer, he says to Melanie, “Man the desk, answer the phones, and put a proper smile on it,” and as he turns to walk away, his back turned to her, he says to me loudly, “Maximilian. It's haircut time.”

I follow him as he teeters from one leg to the other, obsessively running his hands through his dirty hair. His energy is pure madness, but behind the steel door, the room has a banal sense of calm. Its clinical cleanliness and pinpoint feng shui are no coincidence.

As he reaches his oxblood leather-topped partners' desk, at the far end of the room with a forged Basquiat hanging above him, I watch him stoop down to the drawer, move his head sharply from left to right, inhale deeply, fully arch backward, his neck tilted, his hair hanging down his back like chainmail, and let out a contented hum like he’s received medicine to cure pain. All the while, I can hear the low hum of news, traffic from outside, and what sounds like orchestral cymbals seeming to crescendo and diminish. I can also hear music—low, guttural echoes, monastic.

“Is that Jocelyn Pook?” I ask involuntarily, not expecting an answer. And I’m not disappointed.

I start to unpack my gear. Suddenly, he’s close to me.

“Tell me something, M-m-m-m-max,” he fakes a stutter when he’s being mischievous or just plain irritating. “Tell me something, are you involved with that girl?” He snorts mid-cough, pointing outside to Melanie.

“No,” I say promptly, trying to throw him off any scent that I find her attractive.

“Are you sure?” he says.

“Yeah,” I say, breathless, suddenly finding the implication boring.

I can smell the chemical on his lips. He leans into my ear and whispers, “She’s mine, okay, you little rat.” Then he starts laughing, moves right in front of me, and gestures with his finger, pushing it into a hole made with his other thumb and forefinger while still whispering he says, “If anyone’s going to get close to that woman, it’ll be me, do you hear me, Maximus?”

“Yeah, sure, okay, whatever,” I say, moving back from him, suffocated by his intensity.

Cocaine and Stuart don’t mix, but he'll calm down. Maybe we’ll be able to talk about something perfunctory. I long for something perfunctory.

Stuart sits in the captain's chair in front of the large window overlooking City Road. He fidgets awkwardly, adjusting himself in the seat. It’s uncomfortable. I look over at the desk, trying to see how much cocaine he’s got. A little sharpener for me might help me through the appointment. As I’m dampening down his hair, about to take my first section, he says, “Do you know about zombification?” he asks me calmly, like we’re talking about the weather.

“The story of King Da, the incarnation of the serpent, which is the eternal beginning, never ending, who took his pleasure mystically with a queen who was the rainbow patroness of the waters and of all bringing forth.”

“No, I don’t believe I have,” I say quietly, and then I get to work.

As if he hadn't heard me, he asks, "Do you serve the loa?"

“Not really…”

He cuts me off. “The Serpent and the Rainbow, a non-fiction book by Wade Davis. That's non-fiction, did you hear me?”

“Yeah.”

He cuts me off again. “Wade is an ethnobotanist, and he recounts his experiences in Haiti investigating the story of Clairvius Narcisse, who was allegedly poisoned, buried alive, and revived with a herbal brew. A zombie.”

“I see. Oh, yeah, wasn’t there a film…?”

He cuts me off. “Wes Craven directed it. During production in Haiti, the local government could not guarantee the crew's safety for the remainder of the shoot due to political strife and civic turmoil.”

“Right.”

In the silence, I tackle his long-overdue haircut. Because I only see him every three months, there is always a lot of work to do. I have to reshape it completely. When it’s wet, I begin by cutting about half of what I need to remove, and then when it’s dry, I use the sharpness at the very tip of the scissors to carve and slice through the hair. I use a super-fast slashing motion like I’m sculpting marble, periodically stopping to use my hands to check balance and integrity. There’s part of me that doesn’t quite know how I’ve adapted my skills to incorporate this kind of texturizing weight distribution technique. I’ve seen a few attempt it, but it’s not quite the same as my version. When I’m nearly finished, I run a wide-toothed comb through his hair from the nape right up to the crown, the hair billowing after itself, hazy and static. While this is happening, I take my seven-inch blade scissors and simultaneously cut into it as the hair is moving downward. What I’m looking for is to catch some internal hairs that might be carrying the faintest detail of weight, every little tweak essential for balance.

Halfway through, just as I’m about to style and apply product, he says, “Fix me a drink.”

I oblige. Before I can think of something to say, he says, “I want you to do something for me, something I should have done a long time ago, but my vanity stopped me. Ha, my own lousy quest for some unattainable youth.”

I’m not sure what he's on about, but then, I’m never really sure. He turns to face me and looks right through me, his eyes unnervingly sincere and steely, like he’s just come back from war.

“What?” I ask uneasily.

“I want you to get rid of that woman in Chelsea.”

It's obvious who he’s referring to. I play along. “I thought...?” I say, quizzing.

“You thought what?” he says aggressively.

His voice is now somewhat raised. He turns to look at me, water limply dripping from his chin, the combination smell of stale booze and Gucci Rush, his signature fragrance, a heady fusion. “Did you think I'd gone soft in the head? You think this is some kind of joke? Do you think I'm a fool, is that it?”

“Yeah,” I say, not realizing which part of the question I'm answering. Then, “Yeah,” I continue, trying to reassure him, and then nervously, I say, “Yeah. I mean, no. I mean. Yeah, she's a nuisance. But no, you’re not a fool.”

I take a deep breath, partially closing my eyes, hoping I’ve done enough for him to back off. He turns back to the window. I see his faint reflection, his face softening, his eyes glazing over. I know what’s coming: an apology.

“Sorry, Max. It’s been hard, you know?”

He’s telling me there’ll be no more disruptions. And then he says unprompted, "Corruption is the steel of lies."

With a long-drawn-out sigh, Stuart leans over toward the other side of the room. Before I can continue, my comb and scissors poised by his left ear, he has skipped over to the drinks cabinet like it’s Christmas Day.

As he’s making his drink, still with his back to me, his monologue, with all its twists and turns, suddenly seeps into my brain. I’m struggling to figure out why Melanie is suddenly on the hit list. Just as I am processing this information, it’s like Stuart is inside my brain, watching the film unfold. I think he can see my questions before I ask them. I hear the ice cubes kerplunk into his glass, and then, “You have a question?” he says condescendingly. And then a series of rhetorical questions. “Can I hear a question being formed?” “You don’t understand?” “Are you sure?” his voice starting to get louder and more agitated.

Just games.

In a quiet moment with Melanie later, after we have talked about the death of Stuart’s wife, I reveal all. It seems completely normal, lying there together to talk about him and her in the purple dusk of the small hours of a new day. Melanie turns on her side to reach for a cigarette, and her body looks tired, and she is once again inviting me to stay with her.

“This is the last time I’m coming to the studio to cut his hair,” I say.

“You said that last time,” Melanie says as I prepare to leave.

“You leaving?”

“Yeah, I think I am.”

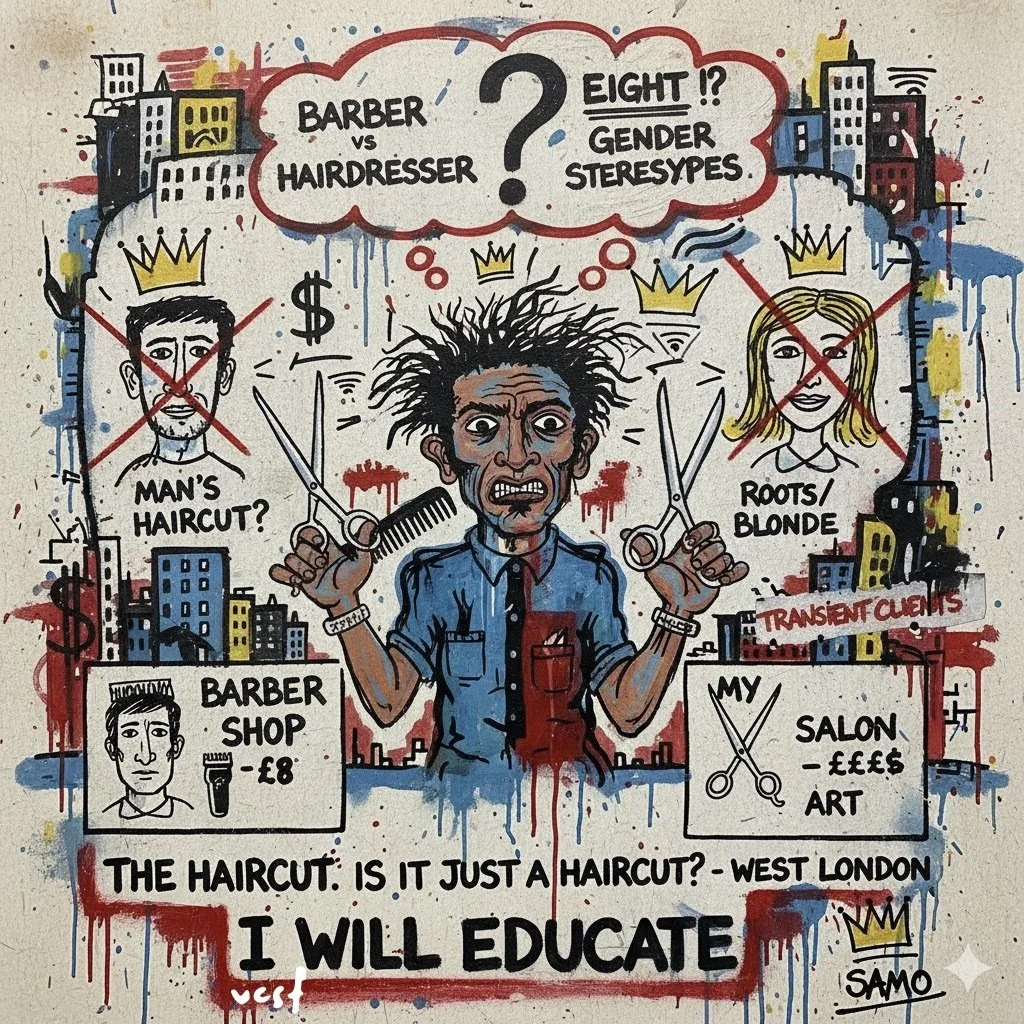

The £8 Haircut and the Gold Bullion Price: A Hairdresser's Debate on Value and Visibility

My first client was a mother of two living just a few streets away. She was very interested in who I was, where I came from, and importantly, how long I intended to “hang around.” She was typical of the type of work I would be doing in the village: a middle-aged woman with reasonably good hair who either wanted to touch up her roots because she wasn’t ready to go grey yet or highlight her hair because she still wanted to be considered blonde. The local area dictated the kind of work I’d be doing in the salon.

I played it safe with her haircut, not wanting to push too hard on the first few visits. I wanted to give the sense that I was doing what she wanted, rather than what I thought was best. I realized, even with this first client, that I was already adopting a softer approach to my work. There were reasons for this. Not least, the last thing I wanted to do was push too hard creatively with someone I wasn’t completely convinced could handle it. Around here, my haircuts and colour work would never leave me. I’d see them all the time, watching them develop in front of my eyes for the better and, sometimes, for the worse. There was nowhere to hide. No more transient clients like I’d been used to in the big salons I worked for. This was a local community, and word travels fast. I’d rather be criticized for doing too little than too much.

During the appointment, she asked me, “Do you do men’s hair?”

“Yes,” I said.

“My husband desperately needs a haircut,” she said, adding, “He always gets it wrong.”

I asked her where he went to get a haircut, but I already knew it was some cheap barbershop. When I heard he paid eight pounds, I wondered why anyone would have a problem understanding why it might be terrible. It’s the same story I hear all the time. She then asked how much I charge, and when I told her, her eyes widened as if I had asked her to pay in gold bullion. But for men’s hairdressing, I wasn’t prepared to negotiate. I think she thought I might. Men’s haircuts should not be any cheaper than women’s, but I would have to wait to implement that kind of pricing structure. This is a debate about what is barbering and what is hairdressing.

It’s typical for men to think they only need to go to the barbershop when they need a haircut, and while I acknowledge that barbers and the barbering industry are highly skilled, it is nothing compared to the discipline of cutting men’s hair when you train as a hairdresser. Why is that? Barbers are proficient in the use of hair clippers, which I have always acknowledged as a skill, but the finer details of someone’s head shape are simply lost on your typical barber.

If you have a straightforward head shape and hair, then a barber might work for you. What is "straightforward"? For me, it is low-density hair that grows in a controllable way, attached to a head shape that is flattering, with ears that are proportionate to the size of the head and almost on the same level. But finding this kind of android, almost artificial aesthetic, is uncommon.

Clippers can be guided around any kind of head shape. You don’t have to understand the many complexities that are involved; it’s a uniform approach to hairdressing. When it comes to using scissors, it’s a secondary tool for barbers. As well as normal scissors, they also use thinning scissors, or thinning shears. These scissors are also used by hairdressers, although in slightly different ways. Barbers use them because they are unfamiliar with how to properly distribute or take weight out of the hair using regular scissors.

Thinning shears are scissors that have one blade with teeth and one blade without. These teeth are little grooves on the blade that will quickly take weight out of the hair. They alleviate excess weight, soften lines, and blend between sections. Each set of shears has a different number of teeth on the serrated blade. Smaller teeth are best used to blend and soften blunt lines created by layering, and wider teeth can be used for taking out weight from hair that is heavy and thick. Like all tools, they need to be used properly. They are used to texturize in conjunction with other techniques to take weight out of the hair and distribute it according to the feel, look, and shape of the haircut. Using them exclusively on men is much easier than on women. With men, you can use them all over the head shape; with women, you have to be very careful where and how you use them. Too high up the hair shaft and too close to the head shape, the hairs will naturally stick straight out.

My expertise relies heavily on the ability to understand the hair—how it moves, how it falls, and to have insight into what it will do when I haven’t styled it, which is something that a huge number of not just barbers, but hairdressers, fail to understand. This primarily comes with experience, but judgment also helps. It’s not enough that the haircut looks good in the moment that you have done it. For me, it has to look good when someone has been out drinking all night and slept on it strangely. I want them to be able to wash and style it and get close to what was done in the salon. There are too many hairdressers and barbers who either forget or simply don’t care about this vital part of cutting hair properly. Great haircuts last, and they grow out so that the shape continues to hold.

I didn’t bother telling her all this. What’s the point? It always feels that when you disclose the real complexity of hairdressing, people look at you and wonder, "What’s the point? Who really cares whether it’s perfect or not? After all, it’s just a haircut.” Men are the ones who seem to adopt this kind of ignorance more readily than women, but it’s not strictly their fault. There is still a stigma attached to men who want to spend time on their hair or even spend the appropriate amount of money on it. It comes from a few different areas, not least because we still live in a world where our genders are divided as protracted, linear identities—stereotypes of a bygone era that only serve to polarize our identities rather than bring them closer together.

While I blow-dried her hair, I drifted off and started thinking about my opinions. Maybe I should say something, because now, finally, this is how I think it should be. I’m no longer working for someone else. I should stand by what I believe. These are the concepts and reasons I want to have in my business. Why shouldn’t I spend the time to educate the clients who come into my business? Isn't this why I have my own business? This is my chance to do things the way I want them. By the time I had plucked up enough energy to open up to her about these pressing, almost inevitable ideas, she was paying and walking out the door. At least I was beginning the conversation in my own head; eventually, it would see the light of day, somehow.

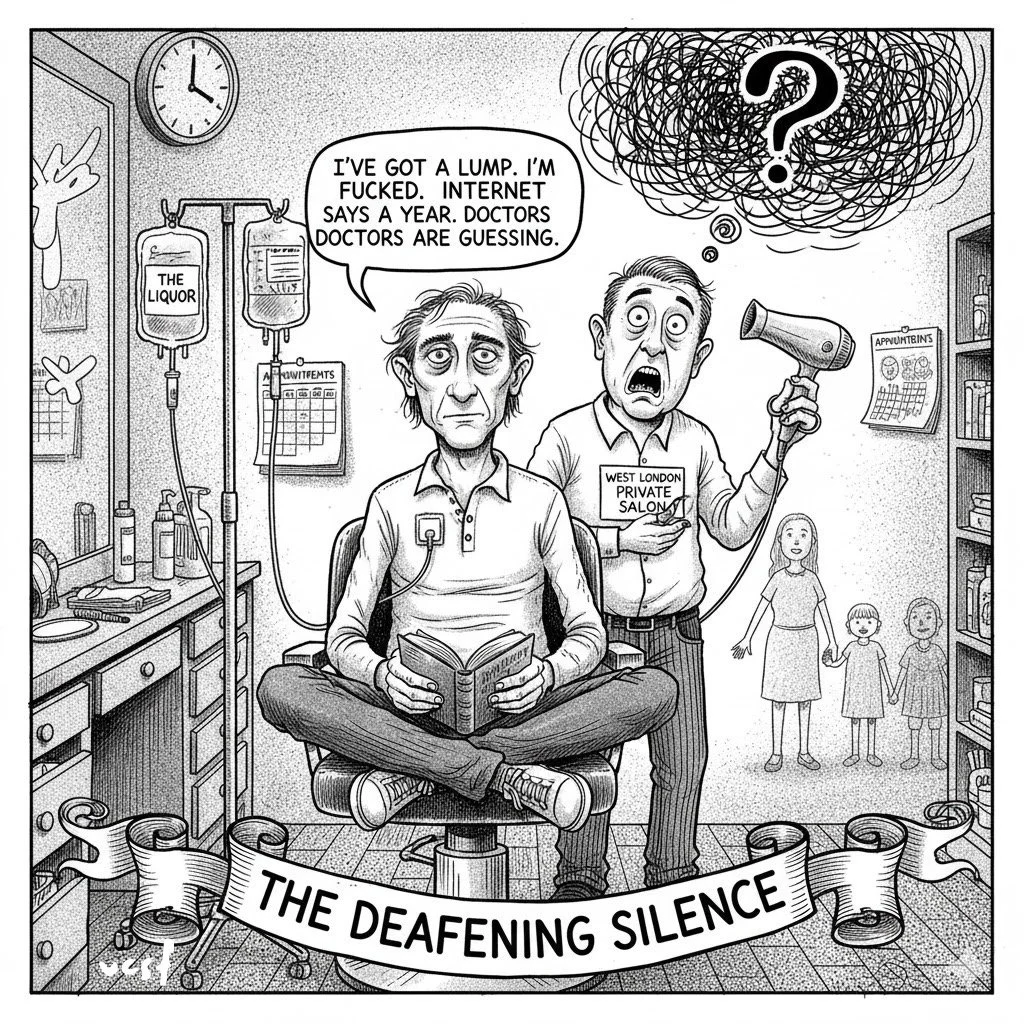

I had a death today….

I had a death today. For whatever reason, nearly all the clients that came in, gave me, shared with me, their experiences with death, near death. Jon, whom I hadn’t known for very long, maybe two years, sat and told me, that at the age of fifty-five, that three months ago he had trouble swallowing. He saw his GP they did the relative tests and they found a lump in his throat. He knew it wasn’t benign he said. In his American low-slung deep voice, he said

‘If there’s a lump in your throat or your stomach or your liver, you’re fucked , you’re gonna die from it. It just depends on how long they can stall it for.’ He sat there crossed legged, like we were discussing a football match. Then he followed up looking me directly in the eyes saying ‘I looked on the internet and it said that I had a year to live.’

I felt my face relaxing into a moronic pause, that I didn’t break out of, for our entire appointment together. I mean, what do I say to someone who had just disclosed that kind of information to me?. I said nothing. I knew there was more to come, he continued, occasionally looking at me, sometimes looking at his feet and rarely looking at me through the mirror in front of him.

‘I mean look man; the doctors don’t really know what they’re doing. It’s all just guess work and you’re part of that guess work and it’s important that you participate in their assessments and their decisions, because it affects what they will do. They try this and then they try that and if one thing works, then they ask ‘how did you find that?’ and if it wasn’t too bad then they do some more of what they’ve already done and on you go until you can get as much time out of it as possible. But no one really knows.’

I stayed quiet. I continued cutting his hair, like he was telling me about something impersonal like his job, or what he did at the weekend, or how his football team were doing in league one. I hoped he’d finished, but the hadn’t. I had a feeling this was just the beginning. He shifted his weight in the chair and then spoke slowly

‘The first time I heard that I had only a few years to live, that was the hardest bit and now that I’ve had time to realise what I’m up against, I’m ready to fight it with all I’ve got.’

There was fight in his words, steel, industry and belligerence, such strength and such bravery and I was humbled and the silence, even more deafening then it had been before, I really felt it. I wanted to contribute to the fight, to help him, but no sooner had I heard the words coming out of his mouth, did I remember that it was just words. ‘My kid has nearly grown up.’ He continued without a pause and then ‘This isn’t a tragedy. This is just something that when you get to the age I have, it’s something you have to be prepared for. I didn’t do anything different. I wouldn’t do anything different.’

I listened to my client Jon , he wasn’t someone who was a close friend and he told me that when he was frank about his condition, because that he said, was a coping mechanism, a problem shared, is a problem solved kind of a theory, but the whole conversation was really difficult to hear. He looked gaunt and sallow, his skin like bacon that was going on the turn, left disregarded, at the back of the fridge somewhere. His strength was spellbinding though, indomitable and not surprising for the person that I knew he was. His pragmatism, verging on comedic, he was almost blasé about his treatment. ‘They hook you up to a port and the feed you the liquor’ He said while I took in the rest of what he had said before. He continued

‘That goes on for about five hours, I just sit and read.’ He said it causally like he was describing wating on a bus to arrive. ‘I don’t feel pain’ He said quickly, like he had read my face, perhaps I’d winced at the idea of having a port into my chest. I asked him if he wanted to talk more about it and he said all he does is talk about it and I said well let’s not talk about it anymore then, and there was a momentary change of subject, and we did our best, both of us to talk about something else. But everything obviously in his life was now affected by the Cancer, so we ended up talking more about it. I didn’t wantto talk about it. He didn’t want to talk about it, but talk about we did.

It was a sunny afternoon, a bit too warm and I could see he was getting tired. I didn’t rush the haircut, I just made sure that I didn’t run over because I knew he still had to get home.

‘You know the thing is’ He said as I was about to finish ‘What choice have I got?. To roll over and die and just give up?, leave my family, knowing that I didn’t even try to fight?’

I had no answer. I just pursed my lips together, gently, solemnly, not really knowing what to say, but knowing he wasn’t looking for me to say anything at all. ‘Let’s not make any arrangements.’ I said like he was asking to book another appointment when he wasn’t.

‘You tell me when you’re ready, and I’ll make time ok?’ I said calmly. I was being as accommodating and thoughtful as I could be. He smiled and I felt like my body was hollow, like there was nothing inside of me, because I knew the situation was so desperate.

As he left, the sun filled the doorway and I again told him to let me know whatever he needed, I’d be there, as best I could.

As I approach the middle of my life, I'm more aware than ever of life's fragility. The worries in my clients' eyes are no longer abstract; they are a reflection of my own fears. This newfound empathy has made me a better listener, a skill I've honed over two decades and believe is the most important a hairdresser can possess. I have learned that a truly successful hairdresser is not necessarily the best stylist, but the one who can connect with their clients on a genuine level.

When I finally hang up my scissors for good, I know I will miss the joy, fun, and emotional intimacy of these moments. I will look back on a career of relationships built on a unique exchange—a fragile, fleeting connection in the vastness of time. I am grateful to have been a part of my clients' stories, just as they have been a part of mine.

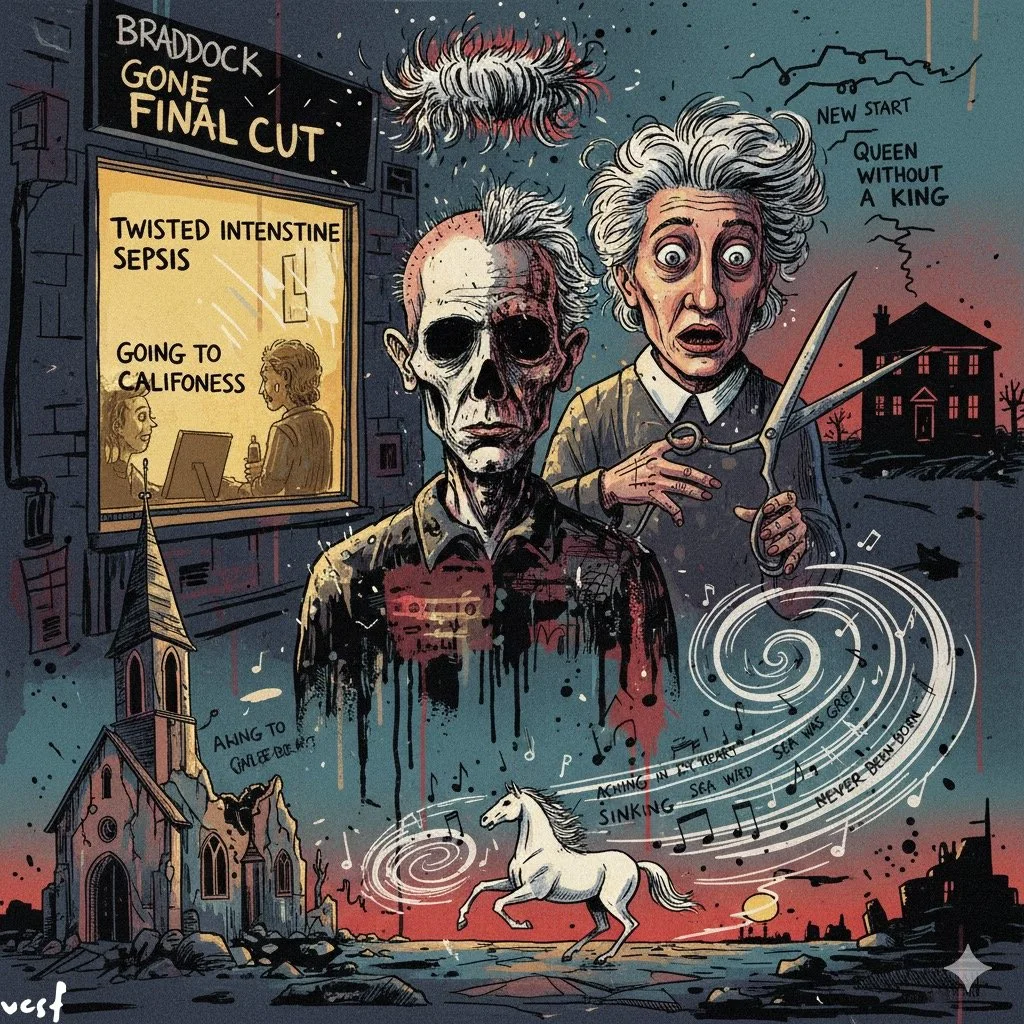

The Final Cut: Braddock's Last Appointment

The news of Braddock’s death hit me like a sudden, brutal blow. It wasn’t just a patron who had vanished; it was a fixture, a living monument to the ten years i had spent shaping hair and a life in this peculiar village. Hearing it from Mick, over a pint in the smoky haze of the thatched pub, the shock made the world tilt. I felt the sickening dizziness of an unexpected void.

Braddock. Gone. Not in some grand, fittingly dramatic way, but felled by the banal, internal treachery of a twisted intestine and sepsis. The stark cruelty of it—the slow poisoning while he was thinking it was merely a hernia, fixable, recoverable. Life, slipping away while he waited for a diagnosis.

What anchored the shock, making it a truly visceral ache for me was the memory of our final interaction. For half a decade, Braddock had asked for the same haircut: a silvery mesh of cool, worked and coaxed into a modern, slightly-fifties style, effortlessly thrown back on his weathered, gaunt face. It was his emblem.

But that last night, with the soft yellow of the golden lamps providing a warm glow against the winter evening outside the salon window, Braddock had been in full flow. His introspection seemed final, a last, comprehensive speech. He spoke of sobriety—the clean break from alcohol and cocaine, the clarity that followed, the new way he saw his old friends. He spoke of growth, or the lack thereof, his lifetime of ‘right’ choices feeling like a faultlessness he despised.

Then, he’d smiled—that cheeky, world-weary smile—and said, “Let’s do something different.”

I took the scissors and cut it all off. Braddock’s signature hair, sacrificed for a change that felt profound, a literal shedding of the old, self-destructive man. It looked good, I remembered. And that was it. The last time. A final act of self-reconstruction just before his body failed him. The memory was a sharp, the final cut in anyone’s mind.

Walking back to the salon that night, after abruptly leaving the company of Mick and the others, I took the long way, feeling obligated to pass Braddock’s house. The lights were on; the car was outside. His three children were likely inside, still expecting him to turn up. The normalcy was a fresh wave of pain.

The group at the pub hadn't understood my reaction. Their faces, as I walked out, seemed to ask, Why on earth did you feel this way about someone from the pub? It was a question that underscores the loneliness of my profession. The world can’t comprehend the relationship a hairdresser has with his clients.

It was as usual a sudden, deep, unexpected loss. I had seen Braddock at his most vulnerable—unhappy, self-loathing, hiding in cocaine, contemptuous of the world while also craving its respect. Our bond was one built on silence, respect, and the ritual of change. I bore witness to his inner turmoil while physically altering his external presentation.

The cruelty of Braddock’s death lay in its timing. Just when he had chosen to change, to live differently, to find the growth he craved, he was erased.

At the funeral, in the quiet, immense solemnity of the church, I finally broke. I sat, listening to the eulogies delivered by other locals, men who knew the Braddock of the village, the schoolmate, the successful neighbour.

As the ceremony ended, "Going to California" by Led Zeppelin filled the space. In that moment, the finality, the unfairness, the pain Braddock must have felt, washed over Larini.

I listened to it all, the acoustic of the church allowing the sound to fill every single space. The words made so much more than they evr had before.

Spent my days with a woman unkind, Smoked my stuff and drank all my wine. Made up my mind to make a new start, Going to California with an aching in my heart. Someone told me there's a girl out there With love in her eyes and flowers in her hair.

Took my chances on a big jet plane, Never let 'em tell you that they're all the same. Oh, the sea was red and the sky was grey, Wondered how tomorrow could ever follow today. The mountains and the canyons start to tremble and shake, As the children of the Sun began to awake.

Seems that the wrath of the Gods Got a punch on the nose and it started to flow; I think I might be sinking. Throw me a line if I reach it in time, I'll meet you up there where the path Runs straight and high.

To find a queen without a king; They say she plays guitar and cries and sings, La la la la. Ride a white mare in the footsteps of dawn, Tryin' to find a woman who's never, never, never been born. Standing on a hill in my mountain of dreams, Telling myself it's not as hard, hard, hard as it seems.

I am a man surrounded by ghosts—clients turned treacherous, life becoming tabloid fodder. I have freedom, but I’m alone. Yet, Braddock's death crystallized something about that solitude.

Everyone can rally to get it sorted, but everything can still be reduced to nothing.

Braddock, with his right schools, right job, right wife, and right dog—who had everything—was still taken.

Braddock’s final, conscious act—the decision to change his hair—remained an indelible mark on me. It was a testament to the human desire to rewrite one's narrative, a desire cruelly silenced. I knew, perhaps better than anyone what Braddock had been trying to become. And now, all that remained was the space he left behind, and the memory of the hair that had been cut off for a new life he would never get to live.

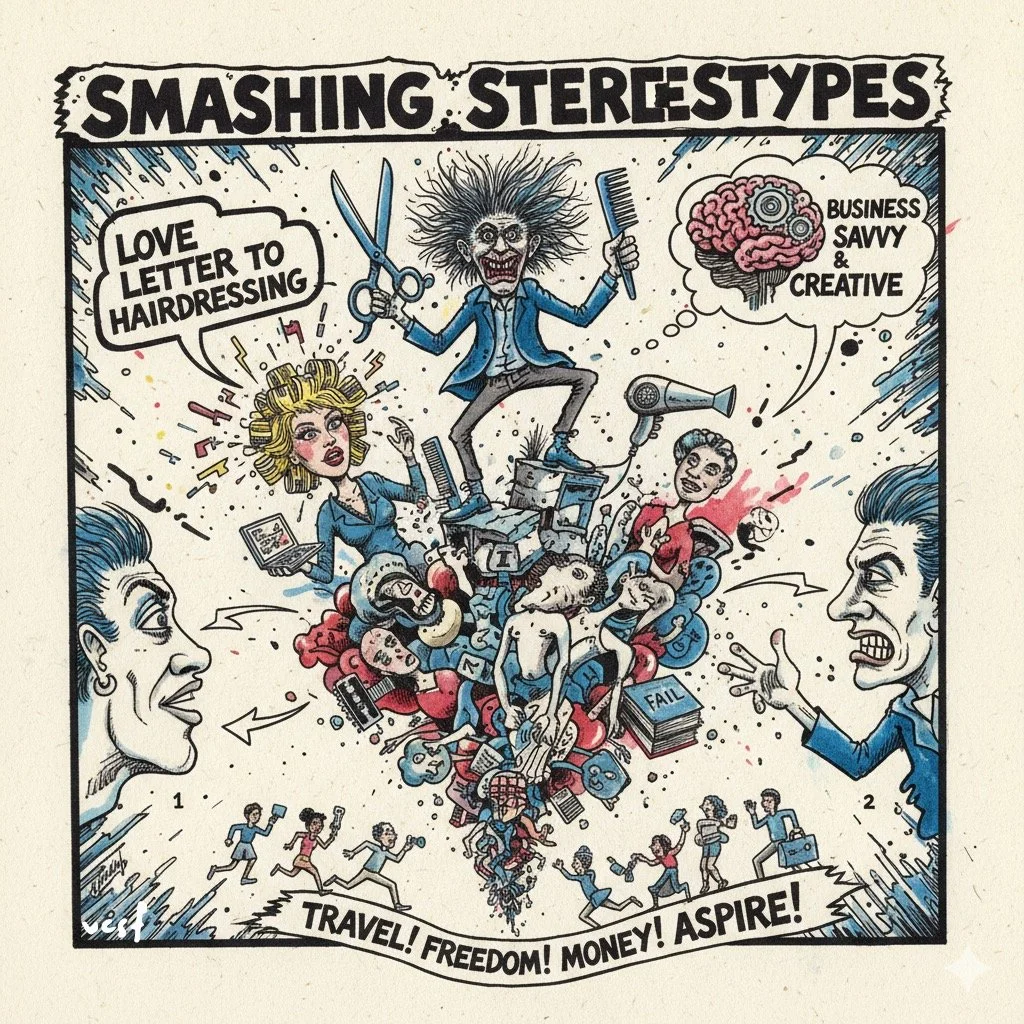

The Unseen Art: Redefining Hairdressing Beyond the Stereotype

For too long, the world of hairdressing has been boxed into a narrow, often dismissive stereotype. It’s seen by many as a fall-back career, a hobby for the creatively inclined who, perhaps, weren't "academic" enough for other paths. But as this recent conversation reveals, that perspective is not only lazy but profoundly inaccurate. Hairdressing is, in reality, a highly skilled profession demanding a blend of artistry, technical mastery, and sharp business acumen.

This transcript captures an illuminating dialogue between two people. Their conversation serves as a rallying cry to dismantle outdated perceptions and present hairdressing as the viable, aspirational career it truly is.

- Keep going……It's lazy to think this, but I just.